Fountain Estate

Fountain Estate lies in the hills beyond Basseterre at about 350 feet above sea level and higher, north of the Fountain River. It is located in what used to be the French part of Basseterre.

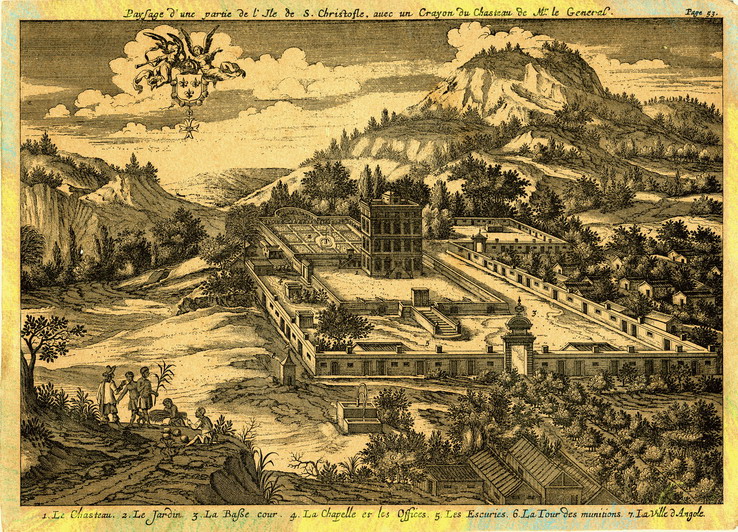

De Poincy

It originally belonged to Pierre D’Esnambuc who probably developed it as a tobacco plantation. After his death it was purchased by Philippe De Lonvillier De Poincy. The governor, who was a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Rhodes and Malta arrived in St. Kitts on the 20th February 1639. He brought with him a number of artisans and skilled workers whom he put to good use in Basseterre but also on his estate where he built a residence that mirrored the auberges built by the Knights in Malta. He also had a good library which included books about fortifications.

De Poincy’s castle was a stronghold. Recently discovered plans for it in the Vatican archives show that it was surrounded by fortifications, a moat and buttressed entrance to its terrace with its gun emplacements and to the house itself. He had stables, storage for forage, a chapel (formerly D’Esnambuc’s residence), a surgeon’s house, a pharmacy, magazines, kitchen and refectory hall and workshops as well as cisterns for water. The house had four storeys and its roof was an observation platform. The grounds were laid out like those of an Italian villa.

A road connected the castle to a sugar estate with a mill. De Poincy was the first on the island to introduce sugar production. Although the water supply proved problematic at first, his skilled workers were able to find solutions and soon the governor had mills on his estates and in the Cayon area. A Dutch merchant attempted a similar experiment in Martinique. However he found himself hampered by the demands of the directors of the Companie des Ilse d’Amerique. While the experiment in Martinique failed, that of D’Poincy which used his resources continued to develop, and before long he had a labour force of about 300 enslaved workers living in a ville d’Angole outside the walls of his castle. Oral Tradition states that it was from among these Africans, that the governor chose those that would entertain him and that these were the precursors of today’s Acrobat troupe.

De Poincy died in 1660. An account of the estate was sent to the Grand Master of the Order in Malta. Seeing mostly debts, some members of the Council of the Order felt that the colonies, which included the French parts of St. Kitts and St. Martin, and the islands of St. Croix and St. Barths, should be sold. Their distance from the seat of government in Valletta and the fact that De Poincy’s nephews were pressing their claim to the colonies made sale an even more attractive proposition. However, De Poincy had left money from his estate in France to allow the Order to continue in possession of the colonies and other favourable reports from Charles De Sales (De Poincy’s successor) put the sale on hold. In 1665 the estate of La Montagne had one mill with three iron rollers and six boilers and was worked by 230 enslaved persons and produced an estimated 145,000 livres of sugar. However in 1665, French Minister Jean Baptiste Colbert and Louis the XIV started to aggressively pursue the ownership of the colonies. As the Order was hoping for the French king’s support in other matters, it was agreed that the islands would be sold to France for 500,000 livres. On the 1st October 1665 the Order transferred its interest to the Compagnie des Indes Occidentals Francaises. Payments were delayed because an individual claimed interest in St. Kitts but as no proof could substantiate the claim, payments eventually started in 1668 and were completed in 1672. The Compagnie was dissolved in 1674. It had run up against the interest of the French settlers who wanted to trade with the Dutch. It is not clear who owned the estate in the remaining years of the 17th century. In 1690, De Poincy’s castle was severely damaged by an earthquake. The land however was still valuable for the cultivation of sugar cane.

Stapleton

Under the Treaty of Utrecht, (1713) St. Kitts was to be retained by Britain. Some of the land was granted to persons who had given service during the war, were favourites of the Commanders or Governor of the island, or were French Protestants who had sworn allegiance to the British Crown. Some lands were leased pending final disposal. The French lands of St. Kitts were considered part of the Royal Patrimony and as such considered the property of the Monarch who could dispose of them as he pleased. But it took a while for the matter of ownership to be settled.

In 1712 Colonel William McDowell held the Fountain estate in trust for General Walter Hamilton who was made governor of the Leeward Islands for a second time in 1715. Meanwhile he had married Dame Frances Stapleton, (the widow of Sir William Stapleton 3rd Baronet) who accompanied him to the Caribbean. The grant through McDowell was renewed in 1717 and 1721. Hamilton died in 1722. In 1726, a commission of three men was given authority to sell the French lands to the highest bidder in parcels of not more than 200 acre. That year, through her attorneys Dame Frances Stapleton attempted to secure the ownership of the estate she had inherited from her husband. She claimed she owned

Three hundred & thirty three acres (viz.) Two hundred & forty acres of Caneland, ninety three acres of provisions & pasture land; which plantation is com’only call’d the Fountain or Castle plantation: and signifys that she has thereon two Sugar Mills a Boiling house & Curinghouse, a Still-house, a Storehouse & a small Dwelling house: that she has besides about a hundred acres of plant-canes & provisions for about one hundred & fifty slaves for six months: that the said Cane-land may be worth Eight pounds Sterling per acre, & the provision & pasture land Six pounds Sterling per acre.

Boyd

As she had more than 200 acres of land as one plantation Lady Stapleton had to give up part of it. Eighty seven acres were bought by John Harries and the rest passed in trust to Gilbert Fleming one of the Commissioners. In 1732, Fleming sold the land that was Fountain Estate to Augustus Boyd in 1732. With successful Huguenot family connections in St. Kitts, young Boyd arrived on the island intent on making his fortune. Although fairly successful, he found he could make a bigger fortune in London, shipping supplies for the plantations. In 1748, along with other associates in London he acquired Bance Island, off the coast of Sierra Leone and started supplying enslaved workers to the North American Colonies.

An account of the hurricane of 1772 suggests that De Poincy's structure may have survived at least in part. It states The dwelling house, a noble antient brick building, flat down, the walls, floor, beams etc falling into the cellars, where a quantity of provisions were destroyed. The account continues to describe the damage in the estate which in turn gives an indication of the value of the estate and the investment made in it: the windmill lost the stocks, points and greatest part of the round house; stable roof off, two pens, one of which just built, down; roof and part of walls of a store room down; a trashhouse and shead over the copper holes, down; the sugar works, sick house and overseer's house very much damaged, by loosening many boards, shingles, doors and windows; and every negro house down; with about two thirds of the crop destroyed

Boyd's business ventures paid off and by the middle of the century his son John was serving as a Director of the East India Company and able to purchase 200 acres and the property where he was to build his home - Danson House. He even took tours in Europe to find art work to fill his new home. The 1817 Register of slaves showed that the Boyds claimed ownership over 438 enslaved workers on their two estates in St. Kitts. On the eve of Emancipation, George Boyd, second grandson of Augustus registered 171 enslaved workers at Fountain. He had bought the property from the estate of his late elder brother but his compensation claim in 1834 was contested by the firm Beckford and Rankin to which the family was indebted.

Berkeley

By 1860s, the estate had passed into the hands of the Berkeley family. Thomas Berkeley Hardman Berkeley, once a member of the Council, was honoured with the memorial in the middle of the Circus in Basseterre after his passing in 1881. The property remained in the family into the mid 20th century. The house which was constructed on the remaining foundations of De Poincy's building, passed into the hands of the J Pereira, the manager of the estate, some time after 1964 and remains in the hands of his heirs.

Wingfield and Romney Estates

Wingfield

The area now occupied by Wingfield and Romney estates, just outside the village of Old Road, was the site of the first permanent plantation settlement in the English Caribbean. It was close to the Kalinago holy places and the fortified buildings along with possible socially unacceptable behaviour may have provoked them into attempting to remove the intruders.

Wingfield Estate was the property of the John Jeafferson, who along with his brother Samuel accompanied Thomas Warner in the first attempt at colonization. In 1660 it was inherited by Christopher Jeafferson who leased it to Charles Pym.

The first permanent plantation settlement of the English Caribbean was in the area now occupied by Wingfield and Romney estates. The settlement had fortified buildings and was close to the spiritual places of the Kalinago which made them feel anxiety over the number of newcomers to the island. It was a place of cultural conflict. The Kalinago offered hospitality but the Europeans often misunderstood the very different social norms of the people they had encountered. This lead to unacceptable behaviour which may have been aggressive and made the newcomers even more threatening.

Wingfield Estate, west of the Black River was the property of the John Jeafferson, who along with his brother Samuel accompanied Thomas Warner in the first attempt at colonization. In 1660 it was inherited by his son, Christopher Jeafferson. In 1676 after he had been on the island for about a month Jeafferson decided he would stay and manage his own estate. He also started preparing to move away from planting indigo and to start building his sugar works. He asked his cousin in England to find him a carpenter and a mason to work on his project. When the hurricane of the 27th August 1681 struck St. Kitts Jeafferson had invested considerable capital in turning his property into a sugar plantation. The hurricane cost him dearly. He lost the roof of his house. About the sugar works he wrote:

I walked down to my new sugar-works, which I had built not long before, about a quarter of a mile or more from my house, towards the sea, to make my tenant’s sugar canes: to whom I had leased fifty acres of land, and had newly begun to make sugar at it, and was then boiling at it, when the storm began. I found that likewise flatt with the ground – the stone wall overturned, and the timber scattered in diverse places, farre distant from the house.

It also destroyed the huts occupied by the estates’ enslaved workers. When it had passed he built a temporary shelter, made sure that one of his sugar works was up and running and planted provisions to that there was food on the estate. A second storm followed five weeks later. Disheartened, Jeafferson decided to return to England in 1682. He restored his building ad eventually leased Wingfield to Charles Pym. The property continued to belong to the Jeafferson family well into the 19th century but its fortunes were now tied to those of the estate that came to be called Romney’s. The connection is most evident in the fact that some of the enslaved registered by Romney were already known by the Jeafferson surname.

Romney Estate occupied the area between the Wingfield River (also identified as the Black River) and the East River. It extended from the coast into higher elevations. It fell in the zone occupied by the English at the time of settlement. The earliest known owner was Charles Mathew, brother of William Mathew, Governor of the Leewards. In 1737, his heirs sold it to Charles Pym who was already leasing the neighbouring estate of Wingfield. Pym’s daughter Priscilla married Robert Marsham, Baron Romney and the plantations was later inherited by their son Charles (1744 – 1811) who became known as the Earl of Romney and hence the name that the estate is known by today.

The plantation manufactured both sugar and rum. According to a report following the hurricane of 1772, the still house, the lower water mill and the overseer’s house were all damaged as were most of the houses of the enslaved. Another serious loss was that of the provisions and the small crops planted by the enslaved. Unlike other estates, which depended heavily on imported food, Romney’s, it was said, produced most of what was needed to feed its enslaved workers. Certainly a drawing of the estate produced in 1822 showed quite approximately 29 acres under potatoes and yams.

Over the years Marsham employed a number of manages to run the estate for him. These included John Julius, John George Goldfrap, who later became the owner of an estate in Trinity Parish, in 1794 and the Rev William Davis. Davis, became a minister of religion in 1791 but continued managing estates as before his ordination. In 1812, he and his sons were suspected of having caused the death of an enslaved woman on Romney’s estate. This caused the Anglican church great embarrassment and in 1814 he left the running of the estate in the hands of his son Edward.

In 1817 Romney hired a new manager. Richard Cardin had been trained in India and had no connection to St. Kitts society which was probably why he had been given the job. A plan of the estate from 1822 shows his attention to detail and his skill in technical drawing. He provided information about the crops planted in each field, the acreage, when it was planted and when the crop would be expected. He showed the location of the works close to the Jeafferson property and the housing for the enslaved its boundaries.

During Cardin’s tenure, he tasked the enslaved woman Betto Douglas with the care of his younger children. One day, Betto’s son suffered an injury and she left these children in the hands of Cardin’s older daughters. Mrs. Cardin was upset and Betto was removed from the job and sent out on hire. She had a hard time making the money she owed Cardin for her hire and renewed an earlier interest in manumission. He would not hear of it and put her in the stocks as a punishment for not making the required payments. Reports of her case and confinement reached Governor Charles Maxwell who asked the magistrates to investigate. They, in turn, recommended that she was once again sent out on hire and that if she could not make the payments she was to be put to do light field work. Once again Betto did not make her payment stating that she had been ill. Cardin had her confined to the sick house from where she eventually escaped in 1826. Cardin paid for advertisements in the local newspapers demanding her return. He died in 1834 around the time of emancipation. Betto’s fate is still not know though her case was brought to the attention of the abolitionist Zachary Macauley in 1833 suggesting that she was still in hiding at the time.

In 1834, The Earl of Romney was the only planter in St. Kitts who wanted to follow the course taken in Antigua and dispense with apprenticeship. Pressure from the remaining planters would not allow him to go through with his plan. However on the 2 May 1835 he released from apprenticeship approximately 75 worker who were over the age of 6 years. (Those under six were automatically freed by the Emancipation Act.)

By 1857, the Earl of Romney conveyed this property to James Dean Roger, planter in St. Kitts and George Garroway, merchant in London probably as a settlement for debts. Roger eventually obtained full ownership. His interests in the island were varied. Not only was he a land owner he was also involved in the sourcing of indentured labour for the estates. It was probably in the later year of his tenure that Wingfield moved away from sugar production and that the planting of fruit trees was started. After the passing of J D Roger, in 1870, the property was inherited by his son Archibald. Captain Roger was a member of the Legislative Council and acted as Administrator of the Presidency of St. Kits-Nevis and Anguilla on several occasions. The estate was then leased to Walter R Boon who had married Archibald Roger's daughter in 1886.

Their son Geoffrey Pearl Boon, a barrister, was the last member of the family to own it. After his death in 1970, his widow sold it to Maurice Widdowson who set up his Caribelle Batik enterprise there. In recent years Widdowson has undertaken the excavation of the ruins of Wingfield and discovered the oldest remains of a rum distillery in the Caribbean.

The Zion Moravian Church

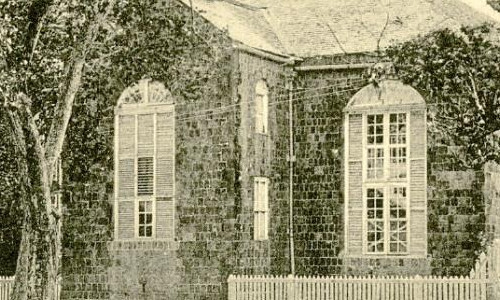

The Zion Moravian Church is a solid structure at the point where College Street and Victoria Road meet. Perhaps its most impressive feature, is its very tall windows. Its interior is modest and uncluttered.

In 1774, while on a visit to England, the American born lawyer, John Gardiner, met with Moravian representatives Benjamin La Trobe and John Wollin. Having gone through a politically strenuous time in St. Kitts, Gardiner was growing disenchanted with both the secular and ecclesiastical authorities on the island. He had already heard of the results achieved by the Moravian missionaries on Antigua and asked that they would consider a similar venture in St. Kitts. He promised access to his own plantation and any other assistance they might require. Bishop Mack of St. Croix was sent to St. Kitts to assess the situation. His report was encouraging.

In 1777 John Daniel Gottwalt of Germany and James Birkby were sent to start the mission. They arrived in Antigua in April and stayed there for six weeks to acquaint themselves with working among the enslaved. They finally arrived in St. Kitts on Sunday 14th June 1777 accompanied by Peter Browne of the Antigua mission. On arrival they were shocked to find that, in Basseterre, the Sunday was not kept as a day of rest and pray but instead all kinds of business was carried on. Gardiner took them to his estate in Trinity where Browne preached to the enslaved. Eventually Gardiner introduced them to the Commander-in-Chief of the island and secured a house for them in College Street. Meetings took place on Sundays and weekdays and alternated between Basseterre and Palmetto Point. Planter opposition was soon laid to rest when it was realised that the missionaries were not encouraging rebellion but rather insisted on obedience and duty. They even had enslaved workers serving them.

In December of that year, the missionaries offered the enslaved an alternative to the revelries that took place on the streets and the estates yards and a significant number chose to attend service on Christmas Day and Old Year’s night. During 1778, Brother Gottwalt visited a number of estates between Basseterre and Sandy Point but most services continued to be held in Basseterre. Meetings specifically for children were started and the congregation continued to grow. The first baptisms took place on the 14th November 1779.

St. Kitts was invaded and captured by the French in 1782. This meant that the island was then under Roman Catholic, French rule. There was some concern for the safety of the Moravian missionaries and plans were set in place to evacuate them to St. Croix. However, Gardiner. who was still their patron, had been appointed attorney general by the French governor and the missionaries continued to enjoy the good will of the new regime.

On the 29th March 1785, the missionaries gave up the house that had been hired for them and moved into a small building also in College Street. It had been bought for them by the Church. Two years later a large stone wall was erected to protect the house from the torrents that came down College ghaut when the rains were heavy. Later a manse was built on the site, but the exact date is not known.

In 1788 the congregation numbered 200 and a bigger place of worship was being sought. The Mission Board’s approval was obtained and the foundation stone was laid on the 21st May 1789 and the church was consecrated on the 11th October of the same year. As the congregation in Basseterre grew, plans were started for activities further afield in Cayon and Sandy Point. Lack of staff hampered the spread of the mission to the various communities but in 1825 Sunday schools were started in Basseterre and Cayon and students, including the children of the enslaved, were taught how to read.

Emancipation was declared in 1834 but the enslaved on St. Kitts met the event with hostility as they resented the four year apprenticeship period that was to follow. Among those arrested for creating a disturbance were members of the church although the missionaries did not encourage rebellion.

By welcoming the enslaved into their congregation, the Moravian Brethren offered them an opportunity to attend church as the enslavers did and to learn reading and writing. As a result by the following year it was recognised that an even bigger place of worship was required especially as the old building had also been subjected to hurricanes, flooding and earthquakes and was in desperate need of repair. A yellow fever epidemic delayed the start of work on the new structure especially after four missionaries died in quick succession. On the 4th December 1837 the foundation of a new school was laid in Basseterre and it was opened on the 16th October of the following year. Finally on the 16th June 1841, Governor Cunningham laid the foundation stone for the new church which welcomed worshipers for the first time on the 30th April 1842. Twenty years later the organ was installed. Henry Booth who came to St. Kitts to install the one at St. George's was a guest at the Moravian Mission House, next to the church. He found the setting very pleasant and described his bedroom as very large and comfortable with a bed in the middle surrounded by a mosquito curtain inside which I have not been able to find a way. Booth arrived before the new organ and had a long wait during which he kept busy by repairing other organs on the island. The one at Zion was his first job. He found that rats had wreaked havoc on it and it required a lot of time and patience to make it sound healthy again. Meanwhile he enjoyed the hospitality of the Rev William Mumford and his wife, at whose table he learnt and enjoyed the local cuisine.

Before a year had passed an earthquake had again caused damage to the building but the greatest disaster came in January 1880 when Basseterre was flooded by torrential rains that fell in the space of just a few hours. The church wall, located at the top of College Street, was subjected to a battering by the rapids that came down from the hills around Basseterre. Thirty members of the congregation were among the hundred that where lost on that day. As far as natural disasters go, the 20th century saw less dramatic events and in some cases the extent of the impact they had on the structure of the church was not always immediately evident. Such was the case when a number of earthquakes shook the island in 1952. In 1971, the church was closed down and services were carried on in the nearby school room. The roof was repaired and it was re-dedicated on the 14th November 1976 by Bishop John Knight. The hurricanes that attacked the island from 1989 to 1998 once again caused damage that was very visible and very expensive.

By 1969, the manse was in very poor state of repair. The building had deteriorated and while efforts were still made to make it habitable, it was recognised that a new structure would have to replace it. In 1977 the Church had to rent a house for the minister and his family and in 1982, on the 250th Anniversary of the creation of the province, a building committee under the chairmanship of Rev Leon Matthias was nominated. Patsy Matthew drew up the plans for the new manse. The Provincial Board approved them in 1983. The old manse was finally demolished in 1986 and the new one dedicated in August of that same year.

The Moravian Church has always been a solid and functional building. In 1948 a new bell arrived at the church and later that year Mr and Mrs H. B. Thompson and Miss Annie Baker donated a clock to the Church in memory of Sister Mary Davis. In 1955 the manually manipulated bellows of the old organ were motorised and in 1992 it was solemnly and lovingly retired with an evening of music and song that said good bye to the old and welcomed the new Rogers 735 organ.

The building and the congregations it served also experiences significant events that were a sign of the changing times. In 1920, the Zion Moravian Church had its first Afro-Caribbean Pastor. He was the Rev. Archibald Theodore King. He was succeeded in 1922 by the Rev. Walter Mansfield Williams who during the labour disturbances of 1935, was one of those attempting to calm the situation and in 1953, Mrs E. Maud Gubi became the first woman to conduct a service at Zion.

Bloody Point

Bloody Point is situated to the west of Challengers Village. It gets its name from the Massacre of the Kalinago that took place in the vicinity.

English and French settlements had been set up on St. Kitts in 1624 and 1625. From the start, Warner and his men treated the Tegreman and his people as hostiles. When they set up their settlement “near to ye kings (Tegreman’s) house” they did not simply build homes, they also erected a fort of “palisadoes with flankers and loopholes for their defense.” However they told the Kalinago that they had done this to watch the fouls they had in the vicinity. The author of this initial account, John Hilton, wondered how Tegreman took this development and whether he actually believed them.

In August 1626, Thomas Warner returned to St. Kitts with over 100 more English settlers, enslaved Africans and provisions. It all strengthened his tiny colony. The fact that he had Africans with him shows that the English wanted to develop the island as a plantation colony and had realized that the Kalinago, with their subsistence agriculture, were not likely to be good labourers.

Tegreman was suspicious and with the increasing numbers of strangers so close to home, he decided to ask for help from the neighboring islands. A woman who lived in the Kalinago settlement is said to have warned Warner. The Kalinago often had women of other ethnic groups living with them often as slaves or servants, so they would have been treated as inferiors.

The Kalinago often prepared for war with a cassava based alcohol. Taking advantage of this Warner struck. Tegreman was killed and those of his allies who managed to escape headed out to sea and to their home islands. It was a devastating rout for Tegreman’s people. A few survived and their presence continued to the end of the century but their numbers were insignificant and the island became a European plantation colony as first envisaged by the Europeans who took it from the Kalinago.

Youth and Community Centre

The Youth and Community Centre on Victoria Road stands on a foundation that survives from the first Government House of St. Kitts.

For a long time St. Kitts did not have a Government house as many of the Governors and Lieutenant Governors were natives who had their own private residences on the island. John Nugent was an exception. He owned property in Montserrat and resided in the Leewards for several years. Soon after his arrival, both the St. Kitts Council and the Assembly agreed to rent the house belonging to Webbe Hobson with all its furnishings for the cost of £100 current money for the first month and £50 current money for as long as the Commander-in-Chief occupied the place. In 1790 the matter of accommodation had to be dealt with again and this time it was decided that a house be rented at a sum that did not exceed £200 current money. The rental of a property for the use of the Governor continued to appear on the agenda of the Council and Assembly for a number of years. Finally on the 21st June 1816 both Assembly and Council agreed to purchase John Woodley’s house, at the northern edge of the town for the price of £4000 current money. The adjoining premises, then belonging to a Mr. Skelling was also to be procured for the sum of £100 per annum. The negotiations were completed in 1817 just in time to receive Thomas Probyn, who bore the title of Captain General and Governor-in-Chief over the St. Christopher, Nevis. Anguilla and the Virgin Islands and who soon set about trying to repair and build additions to the existing building.

In 1832, a committee appointed by the Council and Assembly to “report on what items and other necessaries may be required for the comfort of His Excellency, the Commander-in-Chief at Government House,” found the place “destitute of furniture and other basic requirements.

A plan of Government House drawn on the 10th May 1855 showed a house on a piece of land of a little more than one acre. On its northern side, a one hundred and sixty two foot fence separated it from the Moravian Mission while on the east, a wall measuring three hundred and eighty seven feet shielded it from the traffic of Victoria Road. An entrance gate was linked by a semi-circular path which lead to the two storey house and an exit gate. On its southern side, an irregular fence screened off a number of small wooden houses and on its western side, it was protected by a stonewall that separated it from College Street.

The public areas of the house were on the first floor and these consisted of two grand spaces which were occupied by the drawing room and the dining room opening on to a magnificent gallery to the front of the building. The second floor which was smaller in area housed two small bedrooms, a nursery and the governor’s private apartment which was also surrounded on three sides by a gallery. Large windows protected by louvers let air and light into the master bedroom and while board shutters that were hinged at the top and were held open at the sill served the same purpose in the other rooms.

The house faced east and overlooked a small flower garden. On the opposite side of the road were the cane fields of the Losack plantation. In the back, a number of smaller buildings housed the Private Secretary’s rooms, the servants quarters and the kitchen. Along the back fence, at a further distance were the stables and coach house. The property also contained a cistern and a well, which was 90 feet deep.

In 1858 a Council and Committee room measuring 15 feet by 18 feet was built and furnished. However Council and Assembly meetings continued to take place at the Court House, located in what was then Pall Mall Square.

The flood of 1880 caused major damage especially in College Street. It swept away the wall at the back of Government House. In November 1882 the Superintendent of Public Works, L. M. Kortright submitted an estimate of £550. 18s to the Legislative Council for work required at Government House. Major work was needed in the floor, and sides of the different rooms, the windows and doors. Some interior changes were also suggested. The Committee that examined the report felt that the new floors for the drawing room, dining room and hall were unnecessary instead suggested that, very little patching neatly done will render the condition of the floors of the dining and drawing room perfectly sound and their appearance will be better than with new wood unless the boards were sawn to order and left a considerable time to cure. The floor of the hall should be covered with a new floor cloth covering the whole width. They felt that the additional gallery would diminish the coolness of the bedroom and should not be constructed unless His Excellency desires it. They also recommended that a chandelier should be installed in the drawing room and sidelights in both the drawing room and the dining room.

On the 7th February 1894 Governor Haynes Smith raised the issue of the future of Government House with the Legislative Council. The Surveyor of Works reported that the Government House was almost uninhabitable. The roof leaked and in some places the wood had rotted and was in need of replacement. The building needed painting on the inside and outside. The Governor asked the Council to consider whether to repair the dwelling or build a new Government House with a ball room on the newly acquired Laguerite Estate. He suggested that if the latter option was agreed upon, Government House should be placed at the disposal of the Government Grammar School. A week later the committee appointed to consider the matter recommended that the dwelling be converted into a High School and a new Government House be erected on newly acquired land at a cost not exceeding £3000. However within a short period, economic difficulties made the spending £3000 to £4000 very extravagant especially as the House was only to be used at irregular intervals.

The difficulties being experienced in the sugar market coloured the debates of the Council as did concerns over alleviating poverty and creating employment while still attempting to balance the accounts of the colony. Ball rooms and chandeliers were set aside. Instead of a totally new Government House, repairs to the old structure were recommended. With the advantage of hindsight, Councilor Todd remarked that it would have been better if the house had been kept in repair in past years. The Blue Book of 1896 showed that a tennis court had been laid out on the grounds. No regular gardener was then employed, instead the grounds were weeded by labourers employed on the public street.

.

In 1918, with the end of the First World War in sight, the matter of restoring Old Government House was again on the agenda with the only proviso being that the island’s surplus reached the £10,000 mark. The Governor felt that the proposed plans should be submitted to an architect in England but the Executive Council disagreed as an English architect would know so little about tropical and local conditions,... that his advice would be of little value. Further the portion to be rebuilt is so simple - merely a two storey bungalow, without elaborate reception rooms - that local intelligence should equal to the task. In 1919 Administrator Burdon wanted the work started. He was especially anxious to protect the house from mosquitoes by installing gauze jalousies and wire doors in the dining room. He estimated that the work would take between eight and ten months to complete.

With much needed work at the Cunningham Hospital and the construction of a poor house receiving priority the work at Government House still had not been completed in 1921. However as Governor Fiennes wanting to visit the island, Burdon found himself in a difficult position. He was forced to leave Springfield, which was in a better condition, for the duration of the Governor’s visit and take up temporary residence at Government House. In a telegram he indicated that he was going to make the move but requested permission to retain one back room to lock up personal property and stores also to leave pure bred poultry in locked chicken run. However Burdon did not have any intention of being uprooted a second time and by the middle of the year repairs on Old Government House were started. Work began in earnest and a vote of £250 was devoted to the purchase of furniture. Burdon attempted to accomplish this while on a visit to England but he found that the funds fell short of the cost and he had to request the vote of a further £300

In 1923 Governor Fiennes was to visit St. Kitts for a cricket tournament and expected that electricity be installed at Government House. This meant that another £250 had to be found to cover the cost of a small plant at a time when the Government was already considering tenders for the lighting of the town. Three of the unofficial members of the Legislative Council found thist to be a waste of the taxpayers’ money. Burchell Marshall, the fourth unofficial member, agreed but added that having experienced the comforts of electricity could not oppose the vote. The Union Messenger was incensed.

The occasional habitation of the residence continued for a number of years. One man was engaged to look after it and when the visit of a governor became imminent a team of prisoners was sent out to set things straight.

In 1946, it was suggested that the Girls High School be moved there. The Headmistress, Miss Miriam Pickard had been looking for another location to house the school and had long had her eyes on Government House but before committing to the move she visited the place with Rev. Sunter of the Methodist Church. They discovered that there was a great deal of work to be done to make the building suitable for its new function but both also realised that there was going to be no other option. When the repairs were completed and the move was accomplished with the help of the students and the trucks of Public Works. Miss Pickard set up her apartment in the Governor’s private bedroom suite and a room in the basement became for a short time the meeting room of the Boys’ Club run by the Rev. W. Beckett. The upkeep of the building rested on Miss Pickard and a young lad who was her permanent helper. She describes the work involved in her little booklet on her experiences in St. Kitts. The building continued to function as a school till 1967 when the Girls High School and the Grammar School were merged into the Basseterre High School.

In 1978 the structure went up in flames. Only the stone foundation survived. A modern structure was put over it and a wooden floor put down and new Youth and Community Centre was created. This floor made the venue ideal for dance and martial arts practice sessions. Until recently the grounds were used for small fairs and outdoor exhibitions.

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram