British Enslavement existed mostly in the colonies but the Abolition movement was strongest in Britain. It was there that the laws that limited the trade and introduced the registry of slaves were first passed. The trade in slaves with Africa had been abolished in 1807 and the trade with other slave trading nations ended in 1812 but this had not produced the changes that the Abolitionist had hoped would follow. They continued to press for the end of slavery seeing it as a process that would take time to accomplish. The British Government took the initiative and with the co-operation of the West India interest in London, encouraged progressive improvements in the colonies. These were to include that:

- The enslaved be given religious instruction

- Marriages between enslaved couples to be encouraged and recognized by law,

- Enslaved families would no longer be separated by sale

- The end of brutal punishment – women where not to be whipped and lashes were to be limited to 25 in the case of men.

- Sunday markets were a desecration of the Sabbath and should be held on other days

- Evidence of enslaved witnesses to be admitted under certain conditions,

- The enslaved to be given the privilege of buying their freedom as a reward for thrift and industry.

- Their right to property had to be recognized.

In the West Indies interference from London was met with indignation. The planters said they would reduce productivity and undermine the value of their property. They demanded that they be offered compensation and then amelioration would follow. Being aware that obstinacy might provoke more direct interference, the colonial legislatures conceded on some of these points. While the British Government did not have the resources to enforce its wishes in the Caribbean, the Colonial Office in London, relentlessly exposed abuses undermining the attempts to justify enslavement. In the end it was the Christmas slave rebellion of 1831 in Jamaica that precipitated emancipation. Enslaved workers in Jamaica believed that emancipation had come and that the planters were withholding it. There was violence on both sides with the enslaved receiving the brunt of it. Officials in the Colonial Office were convinced that only complete abolition would preserve peace in Jamaica.

In London, The Reform Act of 1832 resulted in a reformed House of Commons with very few West Indian members. The Colonial Office was faced with a dilemma. On the one hand there was the apprehension that emancipation would provoke bloodshed. Officials were afraid of a repeat of the Haitian Revolution but also sensed that if it was withheld for much longer that too could result in violence. They were also worried that the new House would pass an emancipation law without compensation to the planters and with no security for the colonies. Therefore the Colonial Office took the initiative and declared that amelioration had run its course and that the end of enslavement was necessary to avoid insurrections in the colonies.

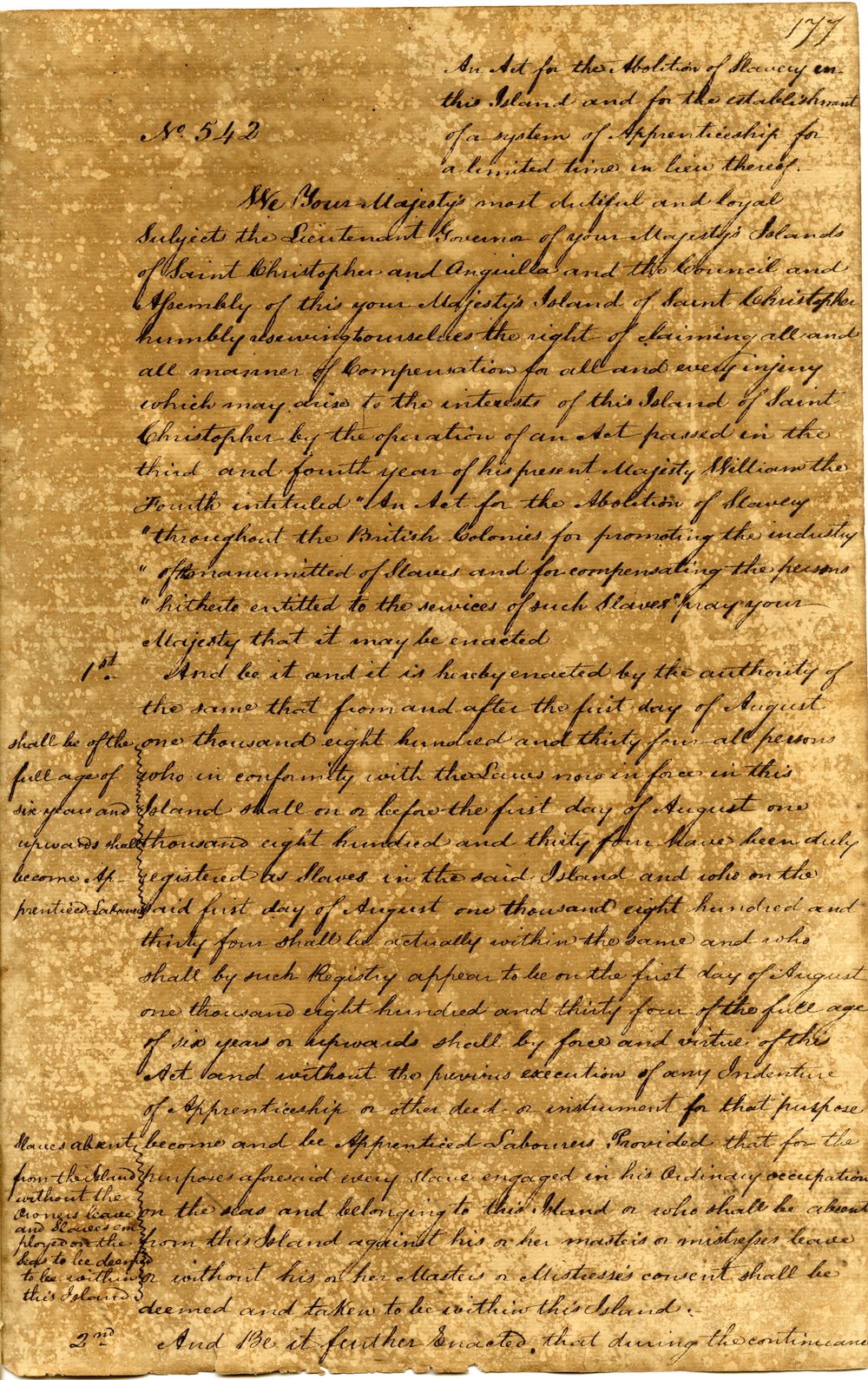

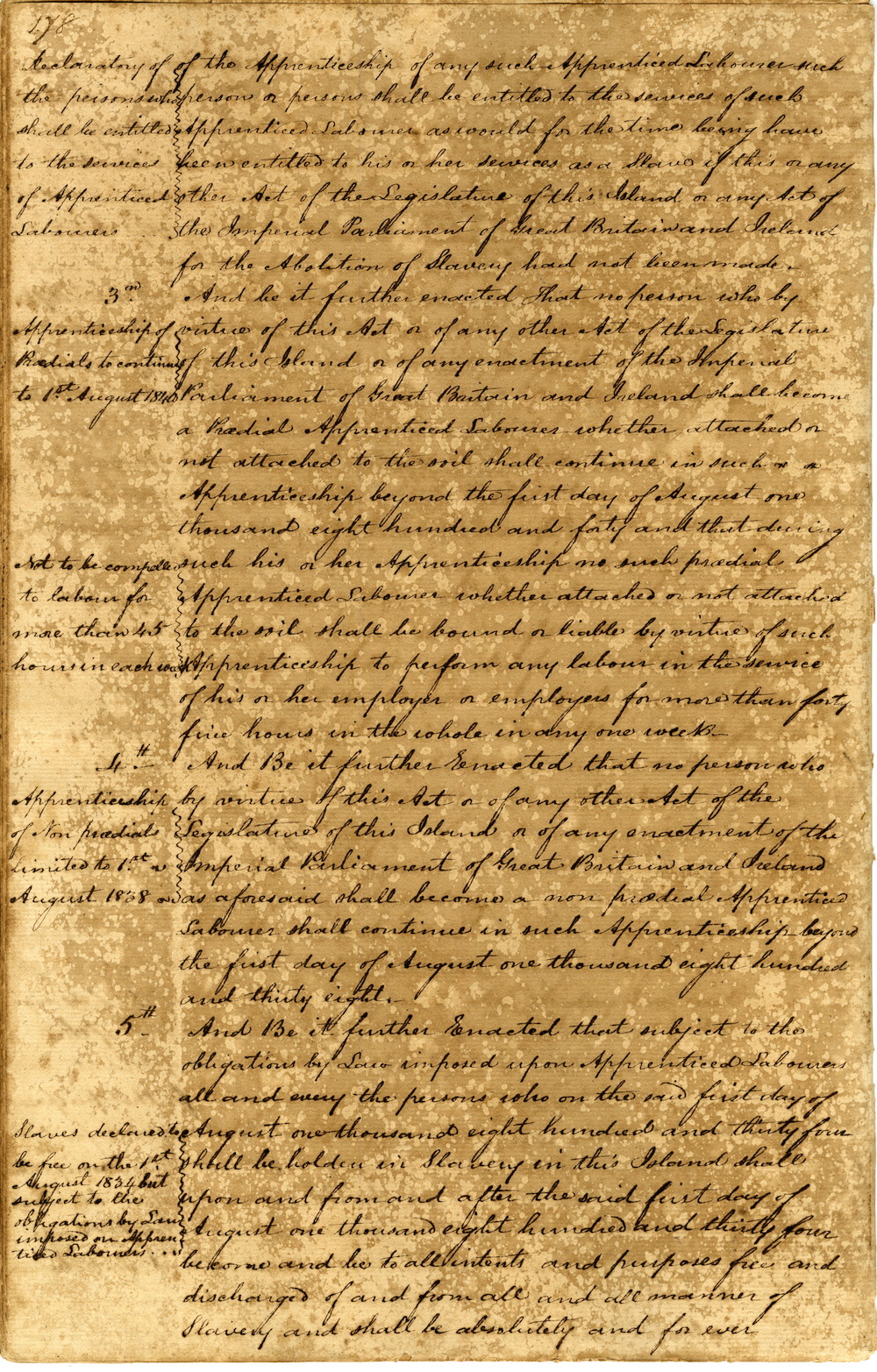

Four plans for emancipation were drafted at the Colonial Office. They had to deal with a variety of expectations, from the use of land, to the availability of labour, to the diversities among the colonies, to compensation and a transitional period towards freedom. The final legislation was drafted by James Stephen son of lawyer James Stephen who lived in St. Kitts from 1783 to 1794. He accepted, in principle, the concepts of apprenticeship and compensation first mentioned in other plans but made some changes. In the case of apprenticeship, it was originally to last for 12 year. In his draft it was reduced to six and the amount of compensation was increased from £15 million to £20 million.

The fact that Parliament even contemplated the compensation was a surprise both to to the Colonial Office, which for a decade had operated under the assumption that Parliament’s only concern was reducing expenditure. However following the Napoleonic wars the defense of the concept of property gained ground within the British Government. The idea that property could be taken away without due compensation was abhorrent.

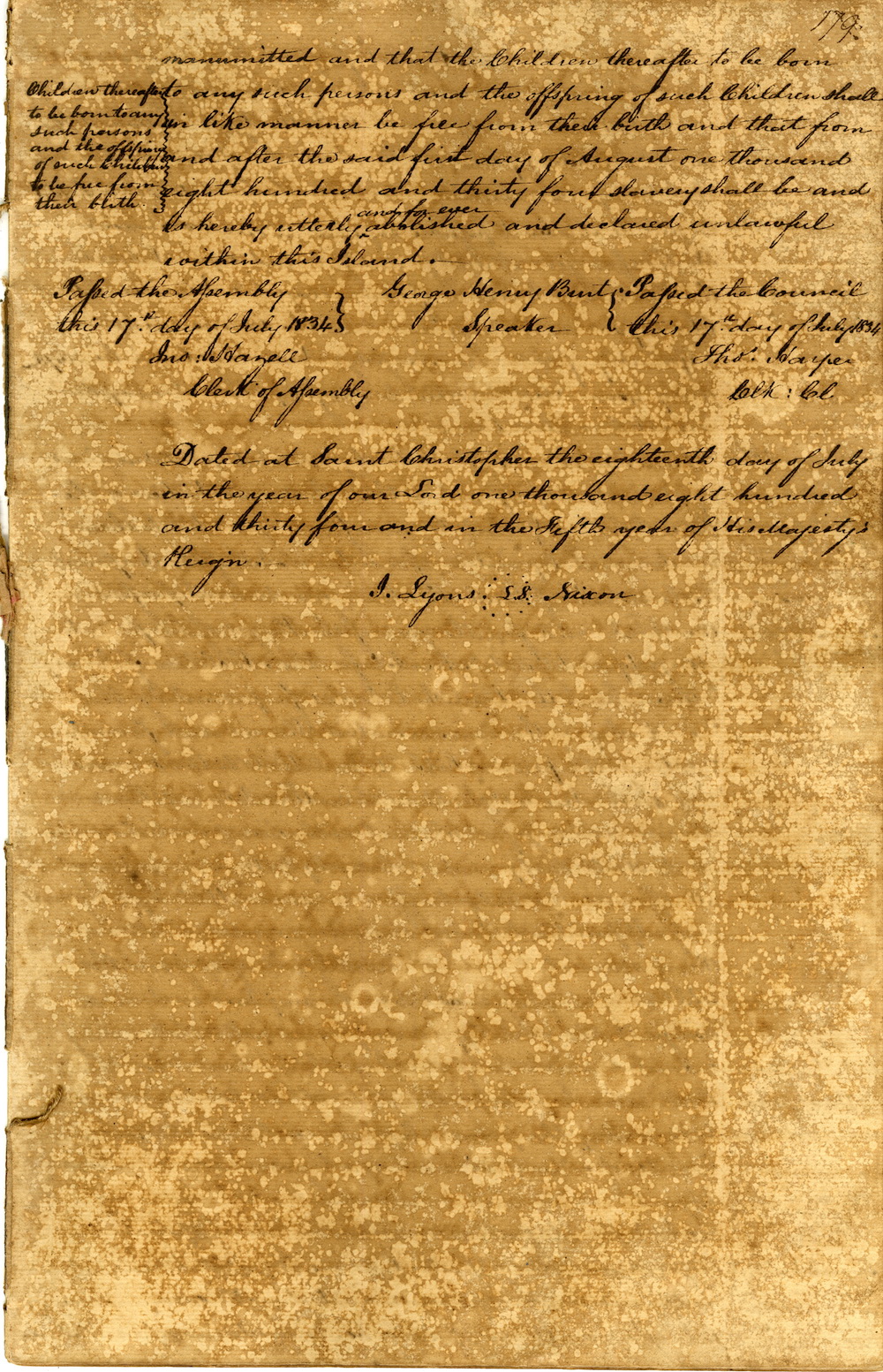

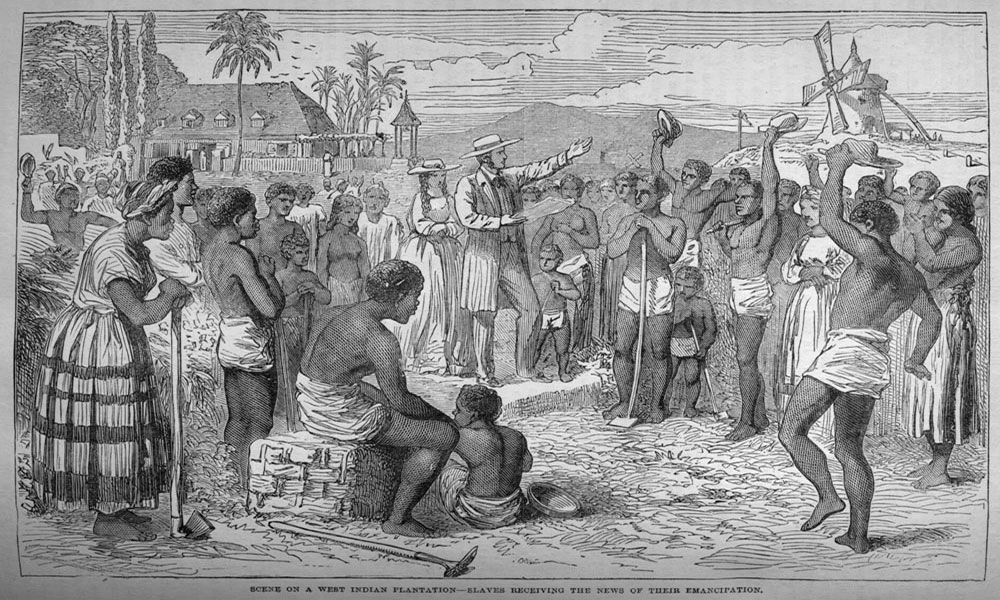

The termination of enslavement in the British empire came about on the 1 st August 1834. The act classified all former enslaved workers as either agricultural (predial) workers or domestic (non-predial) servants. For the agricultural worker, apprenticeship was to end in 1840 while 1838 was the termination date for the domestics. Apprentices were to be permitted to purchase their discharge before the prescribed transition period and employers had to accept a fair payment. The allowances of food, clothing, accommodation and medical service were to continue, In return, apprentice had to give their employers 43 hour a week of unpaid work. Children below the age of six were freed and placed in the care of their mother. If she was destitute, the child was indentured until he/she reached the age of 21. One hundred special magistrates were tasked with the superintendence of apprenticeship and the adjudication of disputes arising out of it.

Although the Colonial Office produced a law to terminate enslavement, it was reluctant to have Parliament interfere in the legislative affairs of the colonies so the Act that came into effect in 1834 established the basic framework of Emancipation. It left to the local legislatures the framing of the rules for Apprenticeship.

Emancipation threatened the social and economic institutions of the Caribbean but those who fought for it were not interested in ending the plantation system nor the social gradations of race and cultural identity in Caribbean society. They, like the West Indian slave holders, believed that Africans and their descendants lacked civilization and therefore needed a strong paternal hand to guide them in the direction of Christian morality.

In St. Kitts, the newly freed apprentices were aggrieved that they had to wait longer for full freedom and many of them refused to work. The authorities were afraid that they would join the ranks of the maroons lead by Marcus of the Woods. The reaction lead to punishments including the deportation of five men to the hulk station Bermuda. It was not an auspicious start for a new era but as the apprentices and their descendants were to discover, it would take much more that a law passed to please the English Colonial Office to change social conditions in the island. There were mind sets that had to be changes that would take time and effort.