The Port of Sandy Point and its Anchorage

Part 1

by Cameron St. Pierre Gill

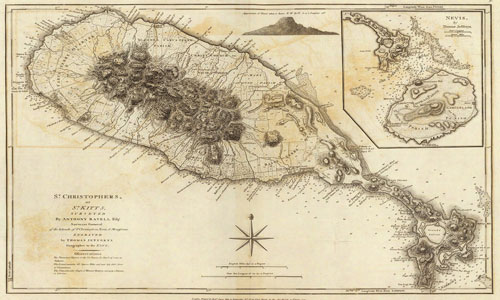

The town of Sandy Point was the first major seaport on the island of St. Christopher (St. Kitts), the earliest English colony in the British West Indies. Many mistakenly claim that Sandy Point was St. Kitts first English town. This is not so, that honour belongs to Old Road, the site of Thomas Warner’s first settlement. When St. Kitts was divided between the English and French, Old Road was the administrative capital of St. Christopher (English St. Kitts) and Sandy Point was the trading centre, while Basseterre was the capital of St. Christophe (French St. Kitts).

Barry Higman has noted that the export driven plantation economy which became a feature of many Caribbean islands first emerged in the Leeward Islands. Early ports such as Sandy Point were indispensable to the growth of that burgeoning export driven plantation economy. As the first major English port town in the Eastern Caribbean Sandy Point became important not only to England's claim on St. Kitts but to her ambitions on the other islands as well. Unlike the other English and French towns on the island, namely Old Road, Basseterre and Cayon, Sandy Point was located next to one of the two boundaries that separated the English and French settlements, whose relationships with each other was always hostile, frequently erupting into armed conflict. The fact that the northern boundary between St. Christophe and St. Christopher ran through the bay at Sandy Point only contributed further to the hostile state of affairs. The Sandy Point Anchorage is one of the largest in the Eastern Caribbean, comparable in size to the anchorages at Basseterre, Oranjested in St. Eustatius, Prince Rupert's Bay in Dominica, Carlisle Bay and Speightstown Anchorage in Barbados. The size of the Sandy Point Anchorage and its location on a contested boundary between two rival European powers caused this anchorage to assume huge strategic importance.

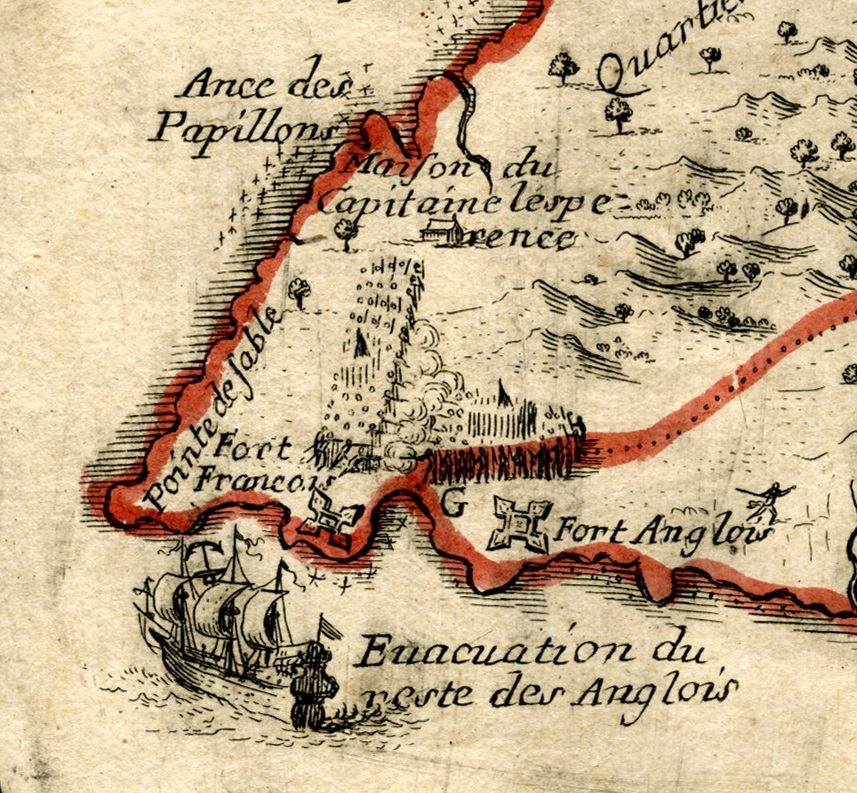

Consequently, within the first century of the island’s settlement the Sandy Point Anchorage became heavily fortified at both ends. The French erected a fortress on the northern bluff of the anchorage (where the village of Fig Tree is located), which is depicted on Etienne Vuillemont’s 1667 Map as “Fort François”. On the opposite (southern) end the English erected Charles Fort, named after King Charles II who had taken the almost unheard of step of financing the fort’s construction out of his own pocket. The King’s actions were indicative of the importance of St. Kitts and more specifically, the importance of the fledgling border town of Sandy Point and its anchorage to Britain's imperial ambitions. After St. Kitts came completely under English control in 1713, Fort François became Fort Charles, a name that still causes some confusion because of the similarly named fort at the other end of the bay.

With respect to that other fort, Charles Fort would begin life as a fort that differed from other early Caribbean forts, including even its younger and now more famous sister, the Brimstone Hill Fortress. Most of the region’s forts began life as simple fortified artillery positions which over time were extended and improved, eventually evolving in some cases into major fortresses. Some notable examples are the Cabrits in Dominica, the aforementioned Brimstone Hill, Fort Delgres in Guadeloupe, and El Morro and San Cristobal in Puerto Rico. Charles Fort, on the other hand, was conceived from the beginning as a comprehensive masonry fortress. There was no haphazard planning in its construction, all of the gun positions are connected by curtain walls that fully enclose the fort, remarkable for a mid to late seventeenth century Caribbean fortification!.

What is equally remarkable is that it took approximately eleven years to complete what would be one of the largest coastal fortresses in the Eastern Caribbean. When one considers that funding for defence works was often a contentious issue between Crown and colonies, such a commitment is impressive. However, all the King’s horses, money and English men could not have made Charles Fort a reality without enslaved African labour. These anonymous labourers and stonemasons have left as testament to their endurance and skill perhaps the oldest surviving intact and original seventeenth century masonry fortification in the Caribbean, a fort built originally in stonework when most other buildings in the Caribbean of the time were being hewn from timber.

Impressive as Sandy Point’s principal coastal fortification was, Charles Fort had one weakness that afflicted, regardless of their size, all coastal fortifications, vulnerability to naval gunfire and encirclement by enemy troops landing on the coast out of range of its guns. However, the limitations in artillery technology of the time meant that in order for their guns to have reasonable range out to sea and properly cover a bay they had to be sited directly on the coast. In 1690, during one of the many armed conflicts between the English and French on St. Kitts, Charles Fort was overrun by the French. The English with the assistance of enslaved Africans dragged guns up Brimstone Hill (which at the time was a limestone quarry) to fire onto the occupied Charles Fort. The artillery fire from Brimstone Hill succeeded in routing the French from Charles Fort and opened English eyes to the utility of Brimstone Hill as firing position. It was from then that fortifications began to be erected atop Brimstone Hill, initially for the purpose of providing a backup defence for Charles Fort. By the mid eighteenth century advances in artillery technology permitted guns located slightly further inland to adequately cover a stretch of coastline and the waters off it. Such progress enabled Brimstone Hill to come into its own, superseding Charles Fort as the primary defence of the Sandy Point Anchorage, although the latter remained an important defensive position up to the late nineteenth century.

While we can pinpoint the dates at which construction of Sandy Point’s major fortifications began and the dates of the first English and French settlements on St. Kitts, much more elusive is the date of the town of Sandy Point’s founding. Early map references to “Sandy Point” refer to a natural geographic feature, the expansive sandy bluff also known as Belle Tete (Pretty Head), not a town. However, a document from the sixteenth century offers a tantalizing clue of at least the period by which the town was already in existence. The Bibliotheque Nationale (National Library) in Paris, France contains a book published in 1667 titled Histoire general des Antilles par les François. By R.P. Jean Baptiste du Tertre. An illustration contained in this French text depicts the 1666 Battle of Sandy Point, apparently one of the major battles that took place that year during war between the English and French settlers. What is interesting about this illustration is that in the background of the fighting depicted a town is clearly shown. Therefore, the Sandy Point referred to in the illustration’s title was not just a beach but an already established settlement. Du Tertre’s depiction of the Battle of Sandy Point is the earliest reference uncovered thus far to the town of Sandy Point

By the nineteenth century Sandy Point had become an important slave trading port and a focal point for trade, in the form of both legal trade and smuggling, as well as communication between the British and Dutch West Indies. John Newton, the slave trader who later claimed a conversion to Christianity, records landing at Sandy Point on more than one occasion in his Diary of a Slave Trader.

Whereas in the French islands, such as Martinique and Guadeloupe, slave auctions typically took place aboard the slave ship, Newton recounts that in the Leeward Islands the auctions occurred ashore. While it is uncertain where exactly in Sandy Point slave auctions took place, whether at Pump Bay, Downing Street or some other location, local folklore among Sandy Pointers claims that an unoccupied lot of land known as The Pound was once a slave market. The Pound is located above the Methodist Cemetary on Downing Street. It has not been possible thus far to verify The Pound’s reputed past but what is interesting is that even some younger members of the community are familiar with The Pound’s alleged association with the nefarious Slave Trade.

The late eighteenth century was a time of heightened tensions in the Caribbean. A French invasion attempt on St. Kitts was expected, it was not a question of if but when. In 1779, a large detachment of British troops were deployed to St. Kitts. The soldiers were landed at Sandy Point and met by members of the Assembly. As the number of troops was too great for them to be adequately housed at the fortresses, accommodations were rented in Sandy Point and Dieppe Bay. By 1796 there were 150 soldiers and officers living in Sandy Point and Dieppe Bay. The majority of them may have been residing in Sandy Point for in 1802 it was recorded that there were 105 soldiers living there.

When the anticipated French attack came in 1782, Sandy Point found itself centre stage with the invading force occupying the town, consequently attracting heavy artillery fire from the defensive positions around Sandy Point. After a month long siege British forces on St. Kitts capitulated to the French but by 1783 the island was returned to the British under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Within half a century slavery in the British Empire was legally ended and by the 1890s the last military garrisons were withdrawn from Sandy Point’s primary defences and other locations throughout the British West Indies. With India’s star on the rise and the British West Indies strategic value on the wane it was seen as no longer necessary to maintain expensive defences at small island ports such as Sandy Point.

However, while Sandy Point was no longer a strategic priority for British and French generals and admirals, the port town would up to the mid twentieth century come to play an increasingly important role in the lives of many people in the islands neighbouring St. Kitts. This we shall discuss in Part Two.

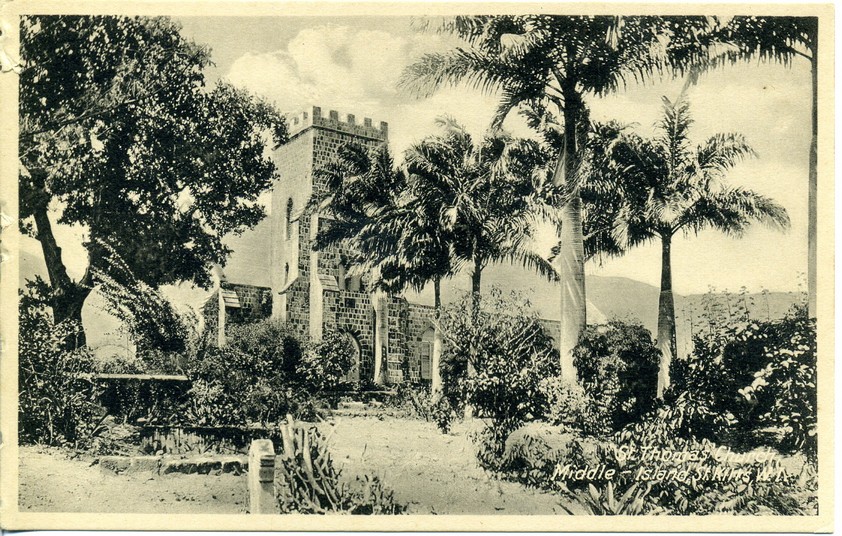

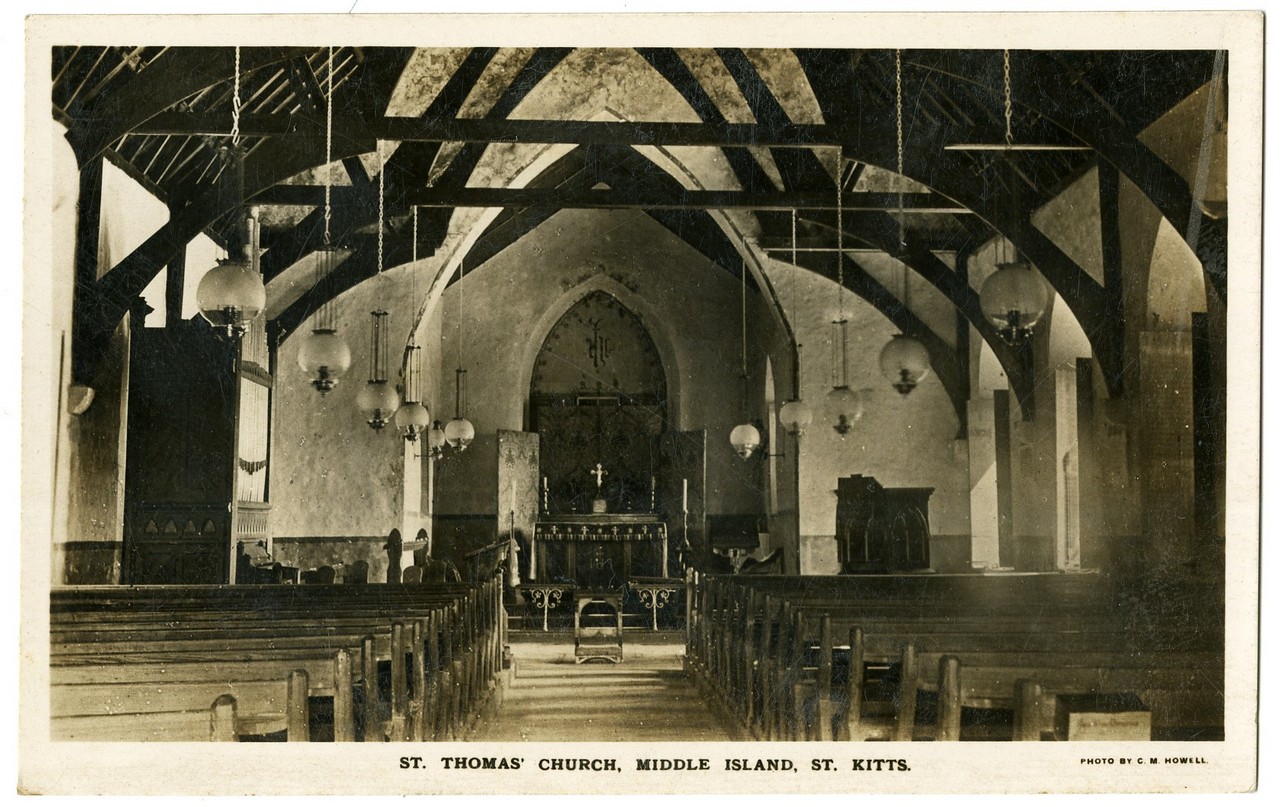

St Thomas Anglican Church

St Thomas Anglican Church occupies the site of the first Anglican Church in the West Indies. The first building would have been made of wood and designed to hold a few English Settlers. Changes were made to it over the years to allow for larger congregations and to rebuild after hurricanes and earthquakes.

In 1622 St. Kitts saw the arrival of an English group of settlers lead by Thomas Warner. They came to build wealth by exploiting the natural fertility of the island. They were met by the Kalinago Chief Tegreman who allowed them to live on the island although regrets soon set in. In 1625, Warner returned to the island with more settlers and was accompanied by Master John Featly, an Anglican Minister. He would have been the first Anglican minister to serve on St. Kitts and the Eastern Caribbean. His sermons reflect a man who was trying to encourage good relations between the colonists and the Kalinago community on the island. In one of them he declared, “Our religion must as much teach the Salvages what we obey, as our precepts whom we obey. Our religion must be as well clad in Sinceritie, as our Strength in courage that so these ignorant infidels observing our religious conversation. May joyne us in a happy Resolution.”

This was not to happen, as in 1626 the Kalinigo were killed and survivors expelled from the island in what was called a preemptive strike. A few remained but control over the island passed completely into European hands.

The congregation of the church was English as reflected iby the names of prominent men in its cemetery. Featly may have had plans to convert the Kalinago and make them part of the congregation but this did not happen. Similarly, enslaved Africans were not welcome into the Anglican Church until the late 18th century when, as the Established Church, it was spurred into action by efforts of Methodist and Moravian missionaries to minister to the enslaved and teach them through their Sunday schools.

The hurricane of 1772 was one of many that damaged the building over the years. This is an account of what happened that year:

Part of the church roof beat in, and a piece of joist, supposed from Mr. Verchild’s estate about 600 yards distant, drove horizontally through the steeple, a little below the cupola, where it now remains. Part of the parsonage house laid almost on its side and the out buildings terribly wrecked. The damages supposed about 200L

When the hurricane began, the Rev Mr. Kirkpatrick and Mr. William Sanders were in the house and staid as long as their safety would permit. Mr. Kirkpatrick then got into an oven, which, to the great mortification of Mr. Sanders, just proved large enough to contain only one person, for he would very gladly have got into it if he could. As soon as the storm abated, Mr. Kirkpatrick quitted his retreat, which was instantly occupied by Mr. Sanders, who was determined to be no longer exposed to the unrelenting fury of the tempest; for he did not know but it might return. However, neither of the gentlemen received any injury than what proceeded from fright

The present church was built in 1860 according to the date in the church tower. It has an extended nave and a tower on its western end typical of British churches. The tower stood at approximately 41 feet and had a base of 14 feet by 18 feet. It was constructed of andesite stone and lime mortar and had an inner and outer wall. The space in between the walls was filled with packed rubble.

In 8 October 1974 an earthquake caused damage to the church. This account was reported by Learnice Mitchell and Dr. Susan M. Kenyon

Shortly before 6 am, Sexton Joseph Duporte was on his way to the church to ring the Angelus for matins. He had just reached Warner’s tomb when the ground shook, scattering stones all about him. Archdeacon Hodge, then Rector for St. Thomas, was leaving his rectory home in Sandy Point to conduct the service when his house shook. He remembers rushing back upstairs to check on his frightened family before hurrying over to the Church.

The church tower collapsed and the roof was seriously damaged. The damage to the tower meant that the bell it housed was left unprotected. The Parish placed it on the floor of the old tower but it was stolen and shipped off island. However the bell was quickly missed and the thieves were apprehended. The vessel carrying the bell had stopped in St. Thomas USVI where it was removed and returned to St. Kitts.

After an extensive fund raising campaign, the Church was repaired and its consecration took place in 2000.

Vambell Estate

Vambell Estate near Sandy Point but actually in the Parish of St. Thomas, takes its name from its earliest known owner Peter van Belle. The estate was located in the English quarter of St. Kitts.

Van Belle

Peter van Belle was born in Province of Holland now part of the Netherlands probably in the 1640s. Very little is known of his early life. With his brother Joshua, he became involved in the Asiento de Negros. This was an agreement between the Spanish Crown and another sovereign power or a private person. Under the agreement, the contractor paid the Crown a specified sum, for a monopoly to supply a specific number of enslaved Africans to the the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The Van Belle brothers acted as representatives of Domingo Grillo and Ambrosio Lomelin. Over time Peter acquired land in Curacao and Surinam where he owned a quarter of the Brandenburg Plantation as well as property in Britain, St. Christopher and St. Thomas. Van Belle was also Director of the Danish Factory in St. Thomas

He married Susannah Durant in 1697, a Hugenot from Nimes in Languedoc, France. The couple did not have children. The couple moved to his property in St. Kitts some time before 1705 shipping his personal possessions and his enslaved workers to Old Road. In his will dated 28 May 1718, Peter left Susannah as his main heir but the property in the Dutch islands he left to Joshua’s children. He also made contributions to churches and institutions in Rotterdam and the parish of St. Thomas, St. Kitts and a sum of £15 for the erection of a church for French Protestants in Sandy Point. In turn Susannah’s will left various sum to her godchildren and to churches including the French Churches in Basseterre and Sandy Point and her personal estate to her brother, Daniel Durant and his daughter Elizabeth who were living in Germany. The plantation and a parcel of land of 18 acre she left to Peter Soulegre and Peter Salvetat who lived in St. Kitts. Governor Hart described Soulegre as “not only the wealthyest man” on the island but in all respects and worthy and discreet gentlemen.”

Peter Soulegre sold the plantation to Ralph Payne whose family had arrived on the island around 1653. Payne died in 1763 and his son also Ralph Payne (later Member of Parliament, Lord Lavington and twice Governor of the Leeward Islands) two years later sold Van Belle and other neighboring properties to William Wells.

Wells

William Wells had arrived in St. Kitts sometime around 1750 with his brother Nathaniel. By 1759 he was a successful merchant but had lost his wife and two very young children. He never remarried but fathered children with enslaved women on his plantations. In 1783 he had three of them christened including Nathaniel, his son by the enslaved woman Joardine known as Juggy.

Sometime before 1789, Nathaniel was sent to live with his uncle who had returned to London, possibly as a companion to cousin Burham. He was also attending school. In his will, William provided for number of legacies, most to slaves that he wanted freed and to children he had had with them but the bulk of his estate, estimated at over £200,000 sterling he left to young Nathaniel. Unfortunately the two brothers died within a space of two years while young Nathaniel the youth, still a minor, had to go to live with another uncle the Rev Robert Wells in Glamorgan.

In 1800 Nathaniel came of age. His uncle Robert was reluctant to give up the estate saying William’s will had not been proved properly. Nathaniel gave him a settlement of £10,000 and took full possession of his father’s estates. The following year he married Harriet Este, daughter of the former chaplain of George II and bought Piercefield manor for £90,000. Vambell estate was part of the marriage settlement. At this point, Wells freed some enslaved workers who seem to have been his relatives or connected to him through his half-sisters. He did not free the rest of the plantation workers. Abolitionist James Stephen criticised his absence from the island which he felt was leading to the ill-treatment of his enslaved workers.

In 1824, Wells and his second wife, Esther sold Vambell and the slaves on it, to John Benjamin Waterson who was leasing it at the time. By 1834 when compensation to enslavers was being calculated following Emancipation, Waterson and his mortgagees, Horatio Adlam and Edward Hardtman filed claims. The decision went in favor of the mortgagees. They were supposed to receive 1842 2s abd 5d doe 107 enslaved workers. It was probabably soon after, that the plantation became part of the properties of James Ewing and Co and remained as such till the 1880s. The company may have been responsible to installing steam powered operations. IT WAS WORKED WITH ????

Ferara

Eventually it was bought by Joaquim Ferara. He was said to have arrived in St. Kitts in the mid-19th century as an indentured servant. Patiently he worked at growing an enterprise which allowed him to start buying estates that were being sold off at low prices as sugar faced one crisis after another. Then in 1918 Vambell along with Chalk Farm were acquired by Messrs. Berridge and Burt for the sum of £2200 from Ferara’s heirs Joseph Ferara, Mrs. McNish and Mrs. Dinzey.

Losada WHU WERE THE LOSADAs

On the 31 August 1935, the estate was bought by dentist Norman Augustine Losada. He was the son of Augustine Moure Losada who arrived in St. Kitts at the turn of the 20th Century. He married Marie Carmalie Deravin, the daughter of the French Consul on the island. A M Losada was also a photgrapher who produced some really beutiful postcards of St. Kitts and he was the founder on a business that became the largest establishment in Basseterre in the 20th century. Norman is still remembered, perhaps not very fondly, for the way he practised dentistry. He resold the land to A M Losada Ltd in 1966 for the sum of $44,000. Sugar cultivation at Vambell was given up. Instead the property was used for cattle rearing and the land remained in possession of the Losada heirs when the Government acquired the sugar lands in 1975.

Douglas Estate

Douglas estate lies north of Basseterre. It was once called Pensez-y-bien.

Douglas

The estate was part of the French Basseterre Quarter but at this point nothing is known about its French owners. By 1714 it was in possession of Colonel Walter Douglas. He was one of seven sons of William Douglas of Baads and his wife Joan. Three of his brothers practiced medicine, with James in particular becoming famous as an obstetrician whose research on female anatomy resulted in several parts of the female pelvis being named after him.

Either an adventurous spirit or the uncertainty of an inheritance led young Walter into the military. He joined William of Orange when he invaded England in 1688 and from then enjoyed the royal favour of the king and his successor.

In 1711 following the murder of Governor Parke in Antigua, Colonel Walter Douglas was appointed Governor of the Leeward Islands. In 1714, when Queen Ann was considering the restoration of the French lands in St. Kitts to the French Crown, Douglas and others sent her a petition asking that if the properties were to be restored that the French compensate them for the improvements they had made to the estates or that they be allowed time to make good their investments.

Two years later Douglas was tried for bribery. He had exacted £10,000 from Antiguans involved in the killing of Parke before publishing the Queens pardon to them. He was sentenced to five years imprisonment, a fine of £500 and removed from the post of Governor.

In 1714 Douglas mortgaged his Pensez-y-bien plantation to Alexander Baxter who, in turn, was indebted to John Ward, an unscrupulous merchant whose conduct earned him a place in the writings of Alexander Pope. There was still a mortgage on the place in 1723. Although Douglas was still alive, he seems to have given up his interest in the property and it was his son John who negotiated with the Commission for the Sale of the French Lands. With the help of Governor Hart who let him £1000 so that he could regain ownership of part of it. In 1726, front of the Commission, John Douglas after describing the boundaries of the estate stated that he

of the said plantation there are about one hundred & thirty acres of plant-canes & about forty of Rattoons a peece of potatos & about eight acres of Negro provisions, & about fifty acres to be planted; that there are settl’d likewise by his leave on between Twenty & thirty acres thereof John England, John Somerfield, James Mitchell, John Waters & Peter Mitchell, being all poor men. The Buildings on the said plantation are a lofted stone Dwelling house in length about thirty nine feet & twenty four & a half in breadth, with a porch fourteen feet in length & twelve in breadth & a shed twenty four feet & an half long & ten broad a stable in length twenty six feet & in breadth fourteen feet, a Coach house of the same length & twelve foot wide, a Kitchin & other offices forty four feet in length & eighteen & a half in breadth, & another outhouse forty four foot long & sixteen broad. All which are boarded & shingl’d. Allso two Boiling houses, one of seven Coppers, in length fifty three feet & in breadth twenty five, the roof whereof is one half tyl’d & the other half thatcht with two Mills & one Still, the other Boiling house of four Coppers, which with a shed joining to it is twenty four foot long & thirty six broad, boarded & shingl’d with one Mill & a Still. For the purchase of which said Two hundred acres the proposer offers to give Ten pounds Sterling per acre, to pay one third down of the purchase money, & to give security for the rest payable at such time as requir’d.”

Another two hundred acres were surrendered to General John Hart.

John Douglas married Susannah Lambert, daughter and one of the heiresses of Michael Lambert and through this marriage and other family dealings Douglas acquired part of the property in the Parish of St Thomas that had belonged to her father. They had a son, who was born about 1732. The great house at Pensez-y-Bien, better known as the White House was built in 1738.

John St Leger Douglas was a member of the Parliament from 1769 to 1783. In 1775 he made what seems to have been his only speech in the House of Commons. At a time when most West Indian planters were concerned about the future of the West Indian plantations given their dependence on North America, Douglas supported sanctions against the American colonies because “it was better to suffer temporary inconveniences than sacrifice the British empire in America to the local interests of any of its constituent parts.” Outside of politics, Douglas bred the undefeated thoroughbred racehorse Goldfinder. He was an absentee owner and his estates in St. Kitts were managed by others. He died in 1783 leaving considerable debts.

His son William enjoyed the estates in St. Kitts as tenant for life but they were actually mortgaged to Sir Thomas Neave, Sir Matthew Tierney, his wife Dame Harriet Mary nee Jones, and Edward Tierney and his wife Anna Maria Jones. The White House as the plantation house was called, was already in existence in 1828 and known by that name. 207 enslaved workers worked on the estate in 1834. Following Emancipation, the compensation for the enslaved at Douglas amounted to £3259. 0s 7d.

Wade

The property was acquired by Solomon Wade in 1859 and renamed Douglas Estate. Solomon Wade took his family to England three years later but continued to take an interest in the properties he owned in St. Kitts. He visited often and hired capable managers and attorneys to run them. In his will, Solomon left Douglas plantation to his youngest son Edwin. Edwin worked as a legal clerk for two years and then returned to St. Kitts. Solomon had hopes that he would eventually learn to manage at least one of his estates. Edwin made the White House his home while he lived on St. Kitts.

The estate became Wade family property in 1909 on Edwin’s passing. Paget Wade and his wife Amy who managed the family concern had great hopes that their son, Charles would eventually do the same. He was artistically inclined and tended not to pay much attention to it until he was forced to do so when his mother died in 1943. In the post war year he was practically resident here. The White House became his home and that of his wife, Mary Gore-Graham who he married in 1946. Charles died in 1958 and his wife continued to live in the house. When government took over the sugar lands in 1975, Douglas estate was among the lands in the acquisition but special arrangements were made for the great house to remain in the family.

Caines Estate

Caines estate is located near the village of Dieppe Bay. It was part of the French Quarter called Capisterre. It is not clear when members of the Caines family arrived in St. Kitts.

CAINES

On the 15th August 1726 Charles Caines offered to buy a plantation in Capeseterre Quarter above Deep Bay from the Commissioners for the sale of the French Lands. It contained 152 acres 3 roods and 7 perches. At the time, thirty acres were in planted canes, twelve acres were in ratoons, one acre in provisions. Caines had a house on it measuring 36 ft in length with two rooms, a kitchen and a steward room with an adjoining chamber. There was also a boiling house of hard timber containing 4 coppers and 2 other houses below the path of 32 feet each with out-house. These were made of hard timber and shingled. He offered £5 sterling per acre. The Commissioners agreed to the sale of 164 acres 2 roods 33 perches of varying quality (none of the land was considered top quality) for £8 sterling per acre but Caines asked for time to consider their price. He was later listed as a puchaser.

The next day Thomas Caines proposed to buy a 29 acre plantation bounded to the north with the sea, to the east with the plantation late of Col. John Hamilton of Antigua, to West with the land of Mary Hutchenson, widow. He offered £10 per acre.

By mid-century Charles Caines Jr had with dwelling house, two store rooms, kitchen, chaise house, poultry house, hog and sheep pen and shed stable adjoining kitchen on his plantation. He also leased neiboring Gibbons the estate of Captain Richard Ambrose Stevenson. In 1772 a hurricane hit the island and the damage caused at Caines estate was described as follows

almost every building on the gentleman's estate was destroyed; a very elegant dwelling house with its furniture, perhaps the most valuable in the island, torn to atoms; all the family wearing apparel lost and the family reduced to great distress for some time. I have been told and I believe truely that two of Mrs Caines' silk gowns were found wrapped around the weather-cock of St. John's church. The crop has suffered greatly. (An Account of the late Dreadful Hurricane which happened on the 31st August 1772… by the editor ([Thomas Howe] Basseterre, 1772) p. 31)

The most notable member of the Caines family was perhaps Clement Caines son of Charles and Judith Crooke, (both died in 1793) who. through her mother was heiress to the Cunnyngham legacies. Clement Caines resided on St. Kitts and was very much involved in the management of his properties, In the General Assembly of the Leeward Islands in 1798, debated a resolution stating that the abolition of slave trade ‘would be oppressive to the British planter, destructive to the sugar colonies and consequently to the British Revenue and of no benefit to the African themselves” Caines who was a member, declared before the House,

The slave trade ought to be abolished. It ought to be abolished immediately. It ought to be abolished for the sake and benefit of the planter. ….

To the African trade may be imputed the unnatural sterility of our female slaves – death without number among our infants – the premature decay, and loss of our ablest people, together with a waste and misapplications of human labour, that renders sugar estates, the most costly, the most miserable, and it is now feared, the most ruinous tenures upon earth…… While advocating for the better treatment of enslaved workers and the end of the slave trade he did not suggest that the enslaved should be emancipated. He published his speech in a book about managing a sugar estate that was very much based on his own experiences. Caines also took an interest in the school for destitute children which housed orphaned white children.

The McMahon map of 1828 names him as the owner of the Caines estate. He became the largest slave owner on the island. In 1817 he registered 565 slaves scattered on various estates owned or leased by him. Unfortunately we do not know at this time, which plantations these were. Some of the transactions that bare his name are very complicated and need knowledge of the 19th century property law to unravel them.

EWING

Before 1853 Caines estate became the property of James Ewing and Co of Glasgow, Scotland. It was still in the hands of his heirs in 1880. Ewing had extensive holdings in Jamaica. In 1834 he made claims for slave on 5 estates in Jamaica but no such claims are recorded for St. Kitts . This could mean that Caines was acquired after 1834. He was not a resident estate owner but the wealth generated by his holdings gave him status and enabled him to achieve a great deal in Glasgow. He was an agent in Glasgow for the imports from the sugar plantations. He was involved I the founding of Glasgow Bank in 1809 and the Savings Bank of Glasgow in 1815. He also invested a great deal of effort into education, hospital management and prison reform.

BLAKE

By the end of the 19th century Caines estate became the property of Daniel Sharry Blake. He was probably born in Nevis but at the turn of the 20th century he was one of the largest land owners on St. Kitts. He was a member of the St. Kitts-Nevis Executive Council and was active in the St. Kitts-Nevis Constitutional Reform Association formed in Oct 1886. The two islands had been united under one presidency in 1881. This organization was probably working towards ending the union. No manifesto of its ideology has been found to date. He died in London in 1910 and in his will he left Caines and Willetts estates to his daughter Lilian Agatha.

In 1916 Lilian married the Barrister, Cyril Malone the son of Solomon Malone of Antigua. He became involved in the St. Kitts Representative Government Association which was attempting to achieve representation in government through elections (with limited franchise). The moving force behind it, was Clement Malone, his cousin. Cyril and Lilian travelled frequently and she was a lavish spender both on herself and in her gifts to others. In St. Kitts they spent their time between Fairview, their favourite house, and Dieppe Bay (later the Golden Lemon). Cyril died of Parkinsons in 1948, Lilian eventually remarried and sold off her property in St. Kitts. Caines estate was among the estates acquired by government in 1975.

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram