Samuel Cable

Between 1829 and 1839, Samuel Cable was the editor of the St. Christopher Advertiser and Weekly Intelligencer, a family-owned newspaper founded c. 1782. He was a member of a free coloured family that had originated in Antigua and had welcomed Thomas Coke to St. Kitts when he was working at establishing the Methodist Church in the region. The Cables, like so many others of their class owned domestic slaves and used skilled slaves in their printing office but were themselves subject to the injustices of the racial hierarchy of the British West Indies.

Newspapers owned by free coloureds were rare at this time. The [Antigua] Weekly Register and The Jamaica Watchman were both outspoken opponents of slavery. The Grenada Chronicle, on the other hand, argued against the abolition of slavery. The Advertiser owed its strength to a larger audience than that of its Kittitian rival, the St. Christopher Gazette. There were approximately 3000 free coloureds, with a strong sense of racial solidarity, as opposed to 1600 whites. Despite the numbers, the Cables were cautious in expressing political opinions.

However in 1823, Samuel Cable was one of forty men who signed a petition of protest which deplored the disadvantaged position of the free coloureds of St. Kitts and which was sent to the British Government. They especially complained about the fact they contributed financially to the public administrations but yet were excluded from all decision making bodies. They also resented the fact that they were not allowed to sit on juries, and were debarred from practicing law. The petition also noted that a school for destitute children supported by public funds to which the free coloured contributed would not cater for children of coloured parents. In describing the situation in the years 1807 to 1810 John Augustine Waller wrote “No property, however considerable, can ever raise a man or woman of colour, not even when combined with education, to the proper rank of a human being, in the estimation of an English or Dutch Creole. They were always kept at a respectful distance.”

A Committee of the Assembly recommended that the elective franchise should be extended to the free persons of colour in the same manner as it is enjoyed by white persons and that restrictive legislation should be repealed. This the Committee felt was ‘the fullest boon that can be awarded by the Legislature without interfering with the long established and necessary policy of this country’. Another petition signed by Cable and fifteen other men was sent to the Council in July 1828 again requested that the contribution of the free coloureds be recognised and laws adjusted to reflect the improved circumstances of that class. In a letter dated 5th October 1829, Governor Maxwell encouraged the Assembly to modify the restriction and disabling regulations of a less enlightened age. Act 524 passed in 1830 granted Samuel Cable and thirteen other free coloureds ‘the right to enjoy all the civil rights, privileges and immunities of other free citizens.’ At the time, it took special dispensation for a free man of colour to enjoy any of the rights and privileges his white counterparts took for granted even when he qualified on grounds of property or education.

In June 1832, The Advertiser expressed approval on the decision of the Antigua Assembly to grant full civil and political rights to the free coloureds. It however complained that such Acts to regulate the trial of criminal slaves, to enforce compulsory manumission, to admit slave evidence which had received approval in Council were still uncertain of acceptance by the Assembly. There was a sense of jubilation when only a few months later the reforms were approved.

In regional coloured circles, however Cable’s paper was not considered “really independent” or one that would “dare, in the face of danger ... to advocate the cause of the oppressed and deeply injured sons and daughters of Africa.” Cable’s first priority in the years before emancipation focused on the improvements desired by his class. Like the rest of his class, he wanted to enjoy the same rights and privileges as the whites and envisioned progress through the legitimate means available to him.

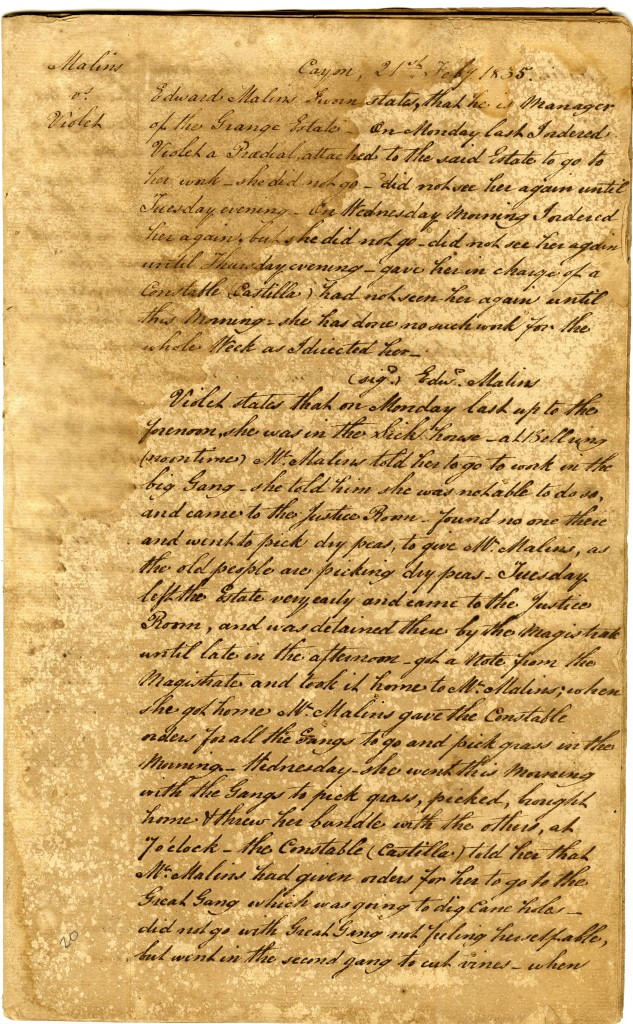

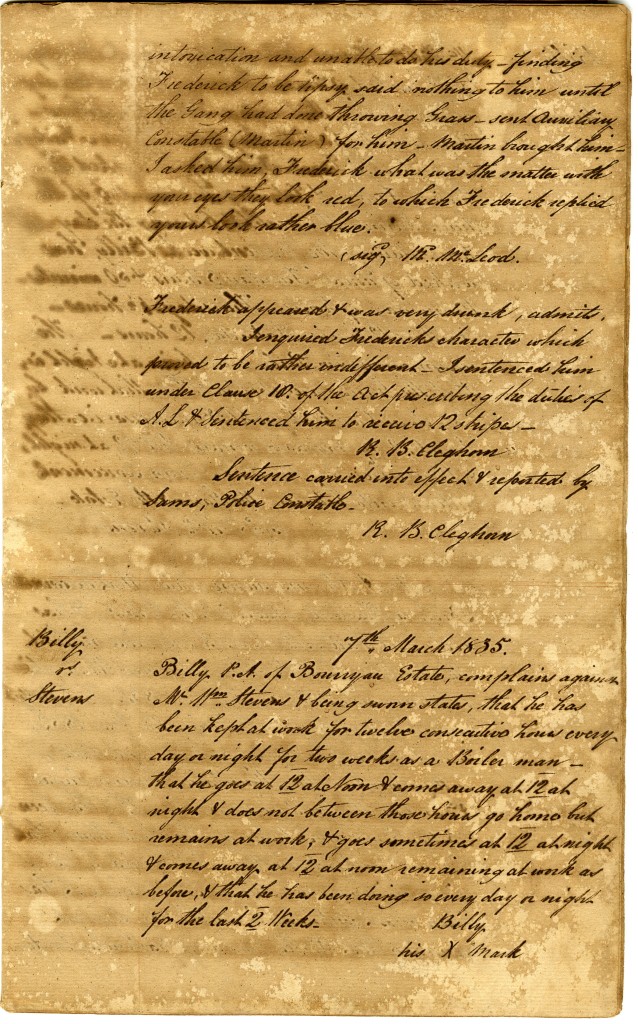

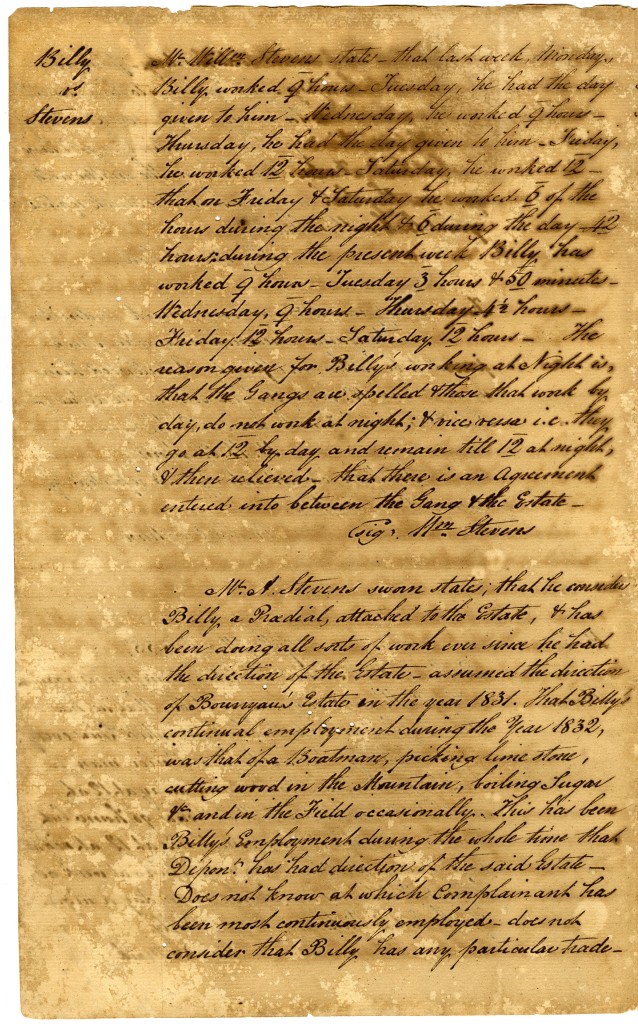

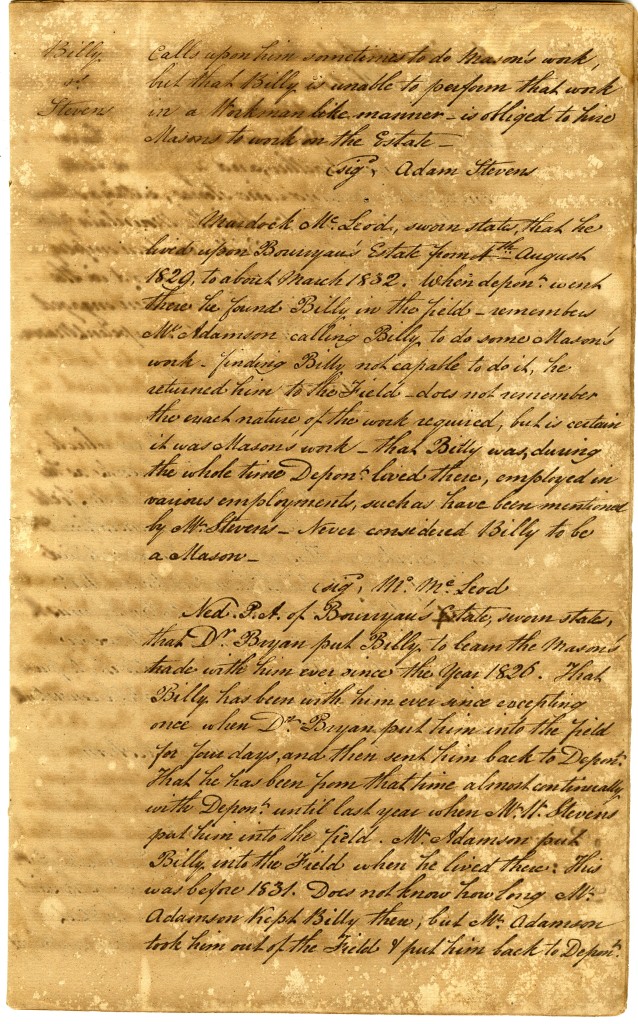

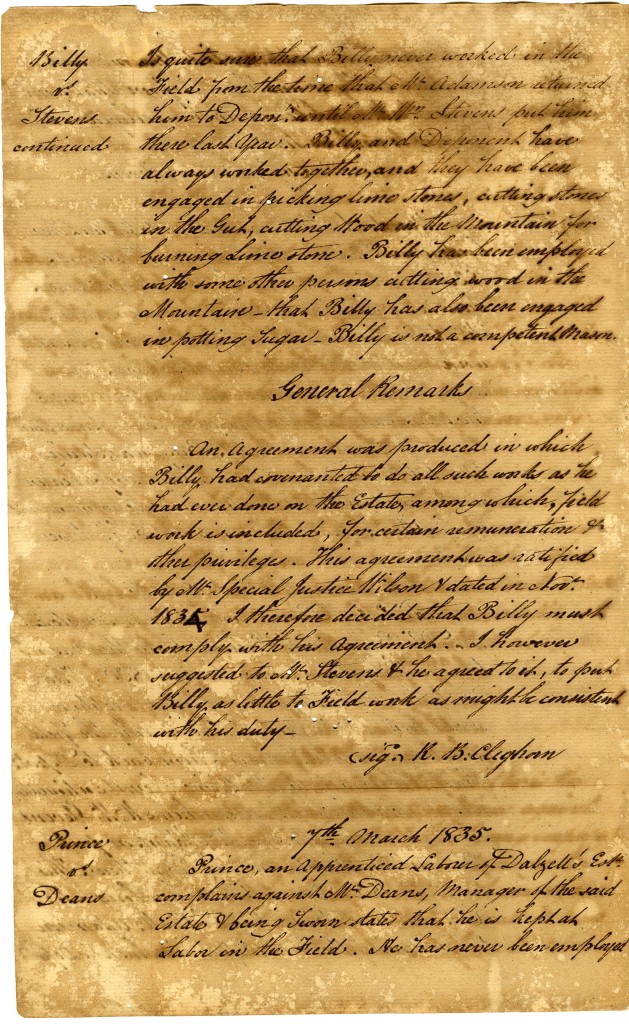

It was not till after the abolition of slavery in 1834 that The Advertiser showed significant political direction on the matter of emancipation. Samuel Cable infuriated the local planters by implying that they were manipulating the justice system. He was sited for contempt, and sentenced to three months in jail and fined £300 for contempt of court in September 1835. The cause was Cable’s questioning of the white planters’ fitness to judge appeals against the workings of the apprenticeship system when they obviously wanted to wrest as much labour as possible out of their former slaves . In July 1835, Special Magistrate William Thomson ruled in favour of two skilled apprentices, a cooper and a blacksmith, who complained of being forced to perform field labour. The Court of King’s Bench overruled the decision and Cable openly criticized the reversal. Commenting on a the outcome of a case, the editor observed

Constituted as the court is, the majority of its members have a direct interest in reaching conclusion to which they have attained.

He was found guilty of contempt of Court and given the chance to print an apology. However the apology that Cable did print was said to have compounded the original insult. In his petition to the President of St. Kitts, Cable expressed concern regarding effect that the decision of the court would have on the plight of apprentices on the island.

The St. Kitts oligarchy had yet to come to terms with a free press. The existence of a free press was not a matter for debate. Newspapers were an integral part of colonial life. It was the extent to which the press was free to air cases of corruption and malpractice in colonial judiciaries that was at issue. Samuel Cable viewed the matter in terms of the freedom and responsibility of the press to report on judicial corruption.

We are but humble journalists, but we trust, we are also acquainted with our duties and sensible of our responsibilities, in such our less lofty capacity. We know the rights of the press; we believe those rights to form one of the most effectual guards of civil freedom; for those rights we are prepared to encounter the spoiling of our goods, the imprisonment of our persons, the peril of our lives.

It took the intervention of the Governor to secure his release on the 18th October 1835. This action was endorsed by the Colonial Office which saw it as an opportunity to take a stand on matters of judicial corruption.

Samuel Cable died on the 5th November 1839 at the age of forty-three years.

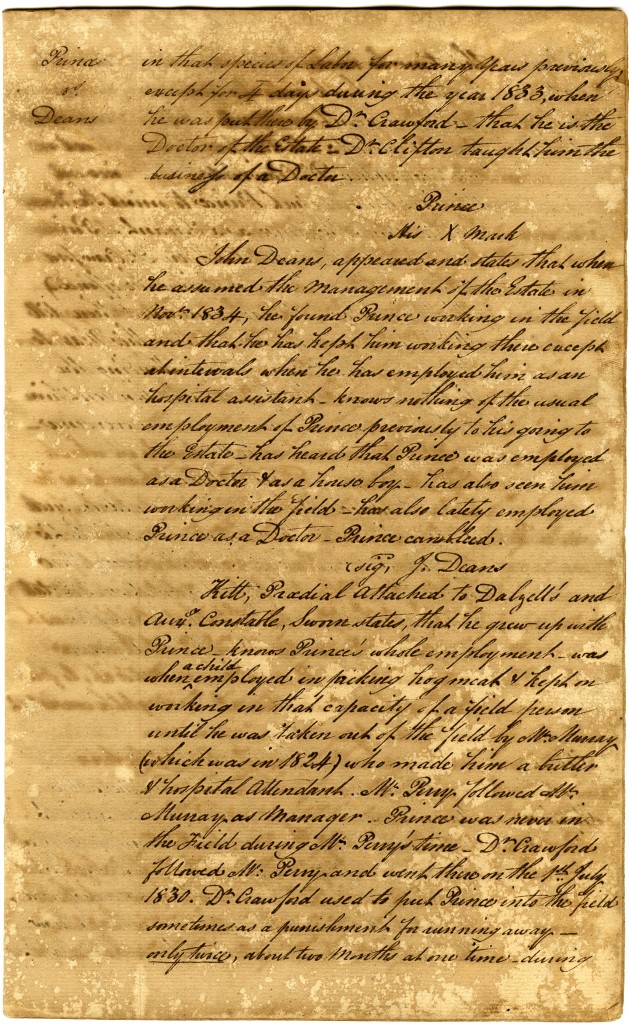

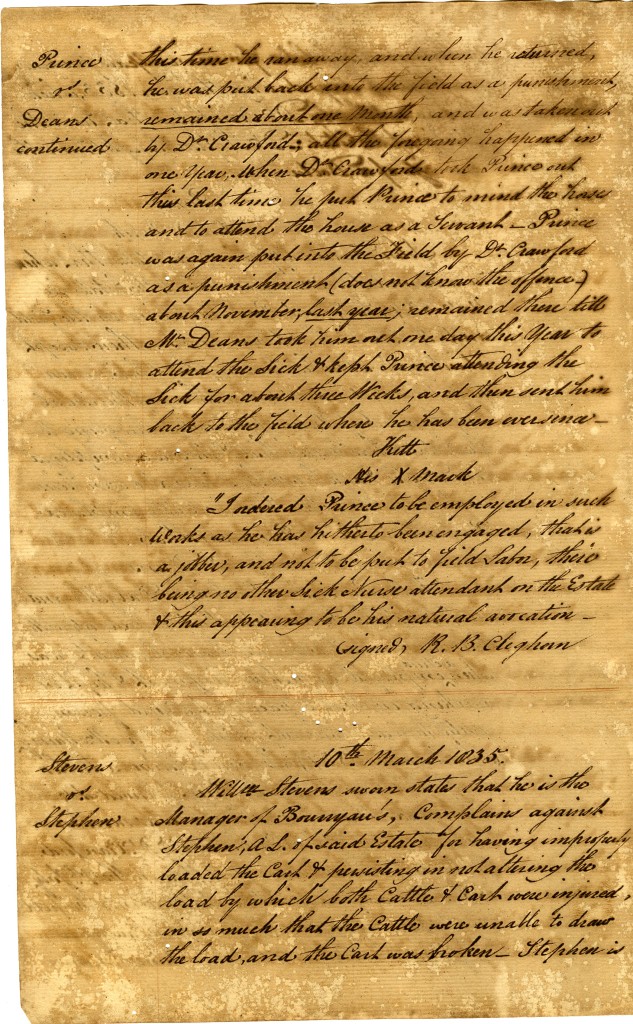

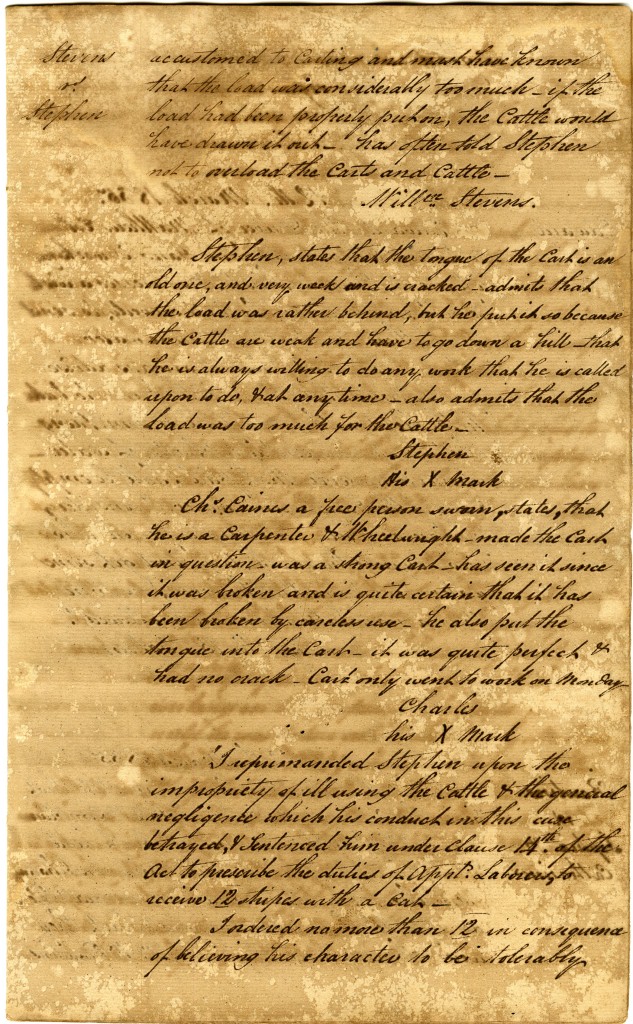

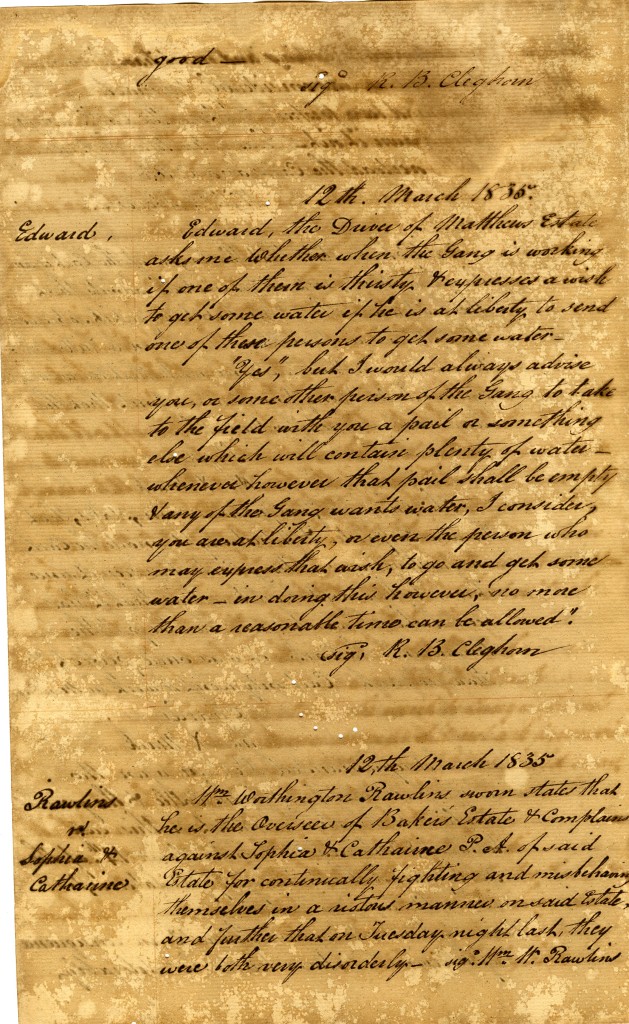

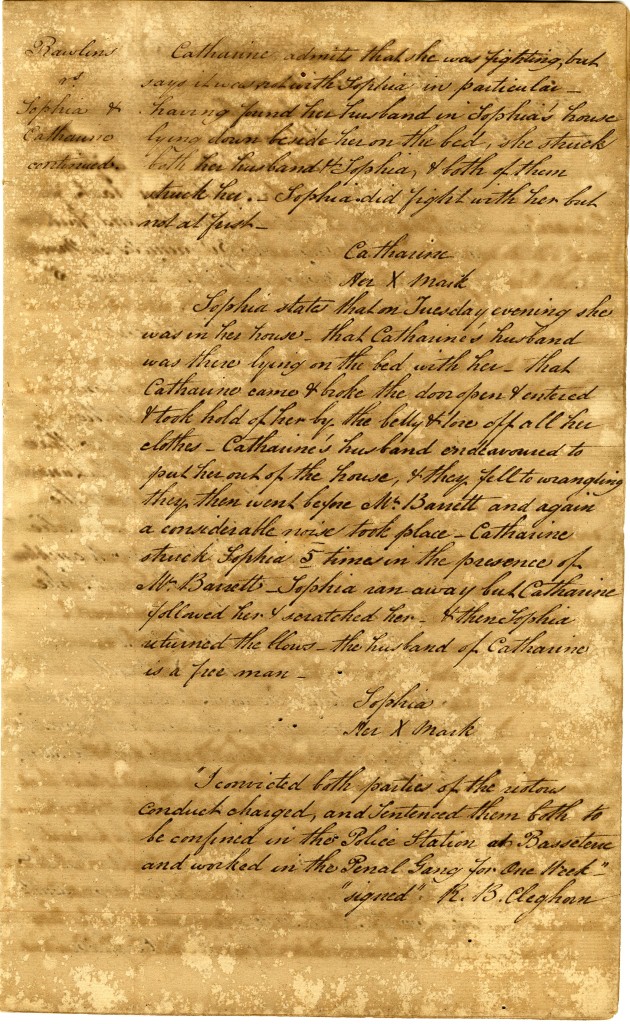

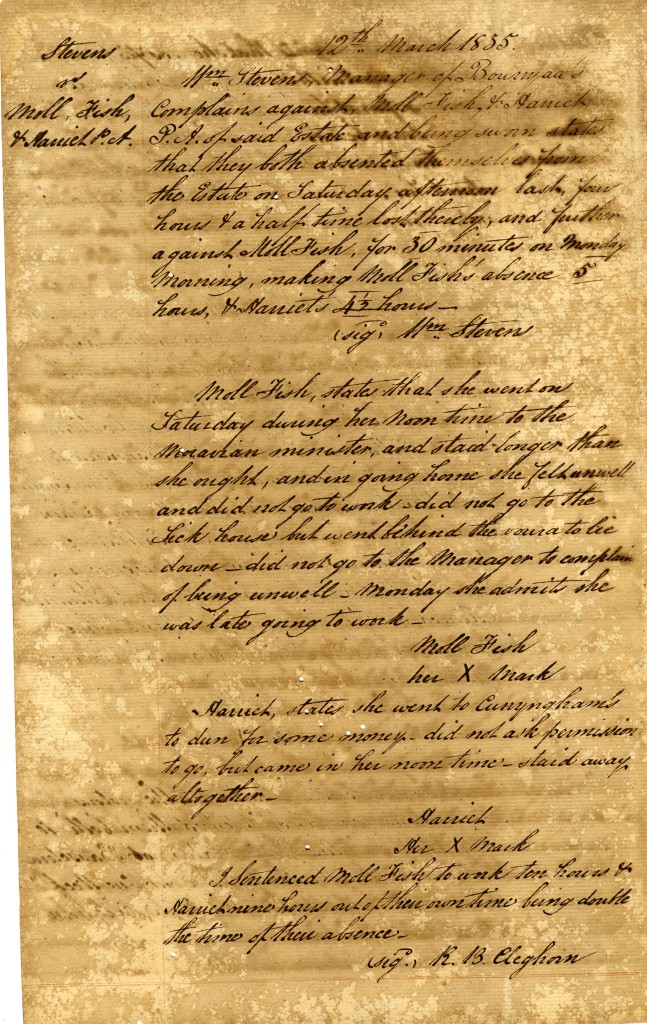

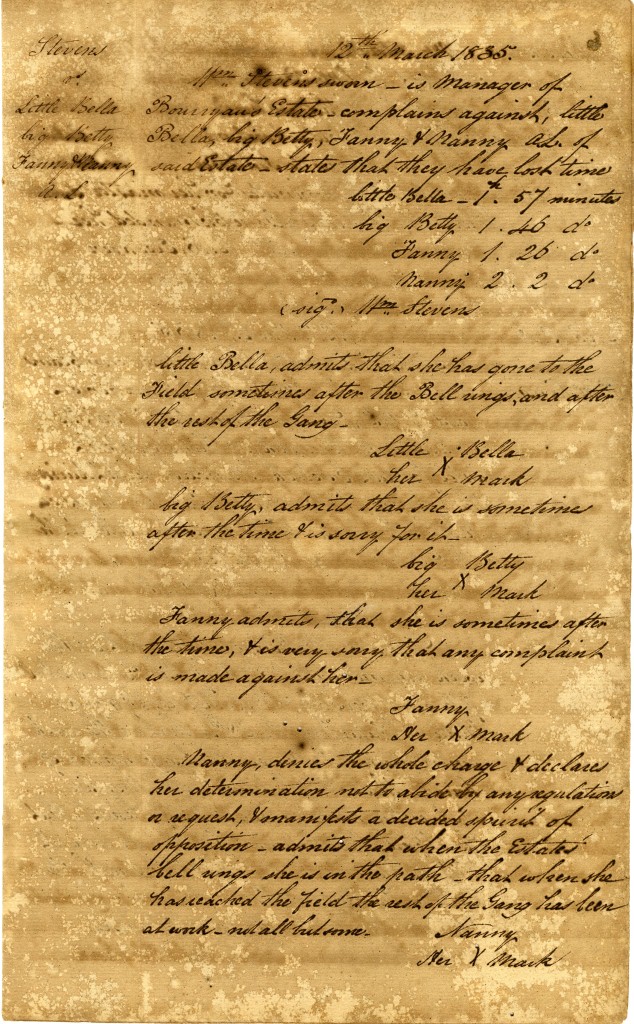

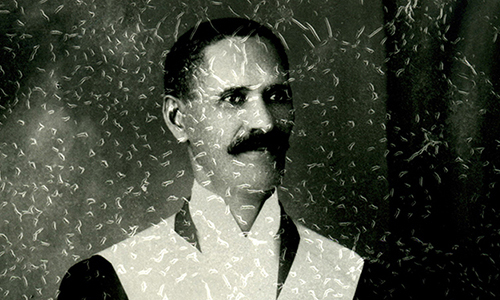

Ralph B Cleghorn

Ralph Cleghorn was a free coloured who was born in St. Kitts. Robert Cleghorn, his white father sent him to England at age five to acquire an education. Shortly after he returned to the island in 1823 at the age of 18, his father died at sea. Ralph returned to England to conclude some business arrangements and made his way back to St. Kitts two years later. He married Maria Berkeley, a free coloured woman on the 24th July 1824. Through the intervention of a friend who advanced him merchandise on the basis of his good name and on his expectations from his father’s will, they opened a dry goods store. At first the business produced an annual income of £1200 but as Cleghorn’s views on slavery became known his business declined. From his father, Ralph inherited cattle and other assets which together with his contacts in England stood him in good stead when setting up his business. In 1829 Cleghorn owned 13 slaves whose ages ranged from five months to twenty seven years. Eventually all were manumitted.

In 1828, Cleghorn was among sixteen men who signed a petition addressed to the Council requesting the reform of “laws and policies conceived in the spirit of the time, centuries ago” which upheld a system that was hurtful to them and prejudicial to the interests of the community at large. In the following year Cleghorn was delegated by his peers to present their petition to the Colonial Office. They were requesting that civil rights be extended to them as a class. This was a time when free coloureds were denied most rights enjoyed by the whites in spite of the fact that they contributed as much as the whites did to the society in which they lived. As an agent for the cause of the free coloureds he spent considerable time in Britain lobbying officials on behalf of his comrades and transmitting to the island important information and recommendations. Having spent most of his life in a more liberal English environment he felt resentment towards the restrictive nature of the society he found himself in. His sentiments towards the West Indian society were expressed in a letter to Zachary Macaulay:

I can most conscientiously declare that I never (and trust I never shall) imbibe any feeling, upon the subject of West Indian manners and policy than that of disgust and opposition, which is only strengthened and increased as I know more of them.

In 1829 Governor Maxwell again expressed concern regarding the disabling laws that still existed in the colony. Finally in an Act of 1830, Cleghorn and several other named men of colour were granted full enjoyment of their civil rights.

It was at about this time that Cleghorn became involved, at great risk to himself, in the Betto Douglas case. Betto was a slave on the Earl of Romney’s plantation who felt that she was being denied the freedom that had been promised to her. Cleghorn was one of the persons who assisted her financially during her period in hiding. Had his complicity been discovered he would have been liable to pay her owner twelve shillings a day for every day of her absence. His involvement was suspected but he and others assisting Douglas had suggested that she might have left St. Kitts.

Yet his efforts continued. Because of his strong anti-slavery views, Cleghorn made frequent visits not only to the Colonial Office but also to the Anti-slavery Society. Under his influence the cause of the free coloured became closely associated with the termination of slavery. They came to realise that as long as slavery existed they would continue to face discrimination and many free coloureds on St. Kitts openly campaigned for Emancipation.

In 1833 Cleghorn and John Berkeley, another free coloured were appointed an aides-de-camp to Governor MacGregor of the Leewards. Two of the white planters nominated to serve with them refused the appointment although they had previously agreed to accept. This was a reflection of the strained race relations that existed in St. Kitts. The Attorney General, Charles Thompson, who had recommended the appointment of the free coloureds was totally ostracized by the rest of white society on the island. The planter class protested “because one is a shopkeeper and the other a lawyer’s clerk and lately from behind the counter and not at all to be associated with.” However the Antigua Weekly Register saw through the class considerations and accused the planters on St. Kitts of wanting “to hold the reigns of office... to the end of time.” The paper went on to defend the men’s “respectability of character, their excellent education’ and pointed out that they had been accepted in “polished society” during their travels in England and on the Continent.

In his letter to Macaulay, Cleghorn described his very limited circle of friends on the island and lamented the difficulties he was experiencing in making a living for himself and his wife. In order to circumvent the boycott of his business he had placed its running in the hands of another person. Even this person was expressing concerns that through his association with Cleghorn he to would become a target of unpopularity. His letter mentioned vacancies for the posts of Provost Marshall and Stipendiary Magistrates and he expressed the hope that he would be considered as a candidate. He especially wanted to serve in a post “beneficial to a class of people whose interest I have espoused even to my own prejudice.” In 1834 Cleghorn travelled to England seeking the appointment of Provost-Marshal of St. Kitts.

Meanwhile the Emancipation Act came into force. Cleghorn’s view was that ‘immediate and unconditional freedom’ should be granted to the slave population. Since that was not likely to happen he accepted the Emancipation plan as the ‘best approximation yet proposed’. He warned however that

Slaves will not easily be brought to agree to any plan which shall preclude their unrestricted admission to entire emancipation, especially the emancipation of the will - enabling them to select their own employers.

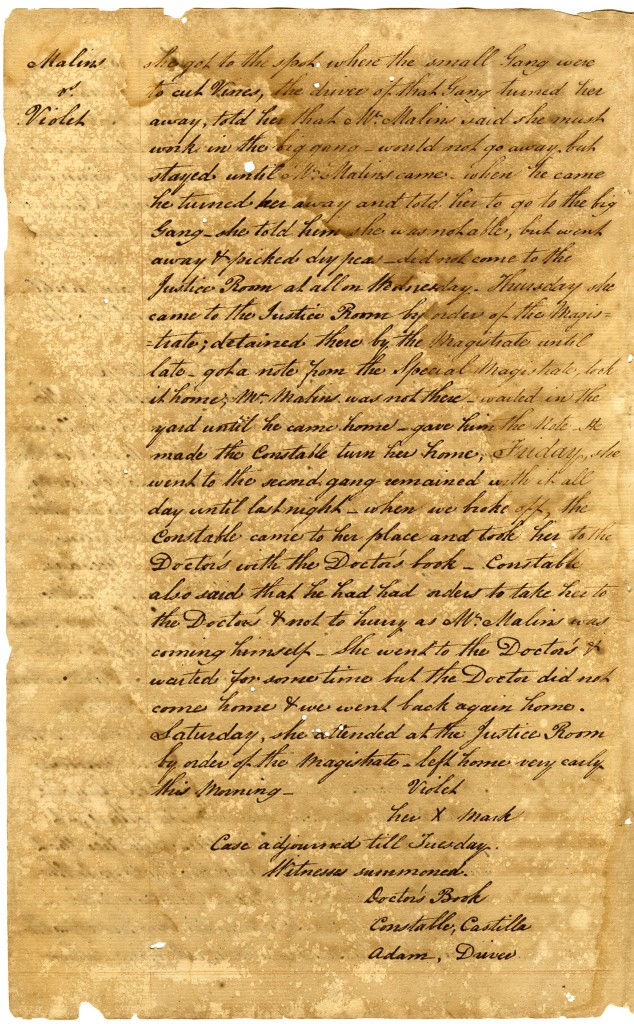

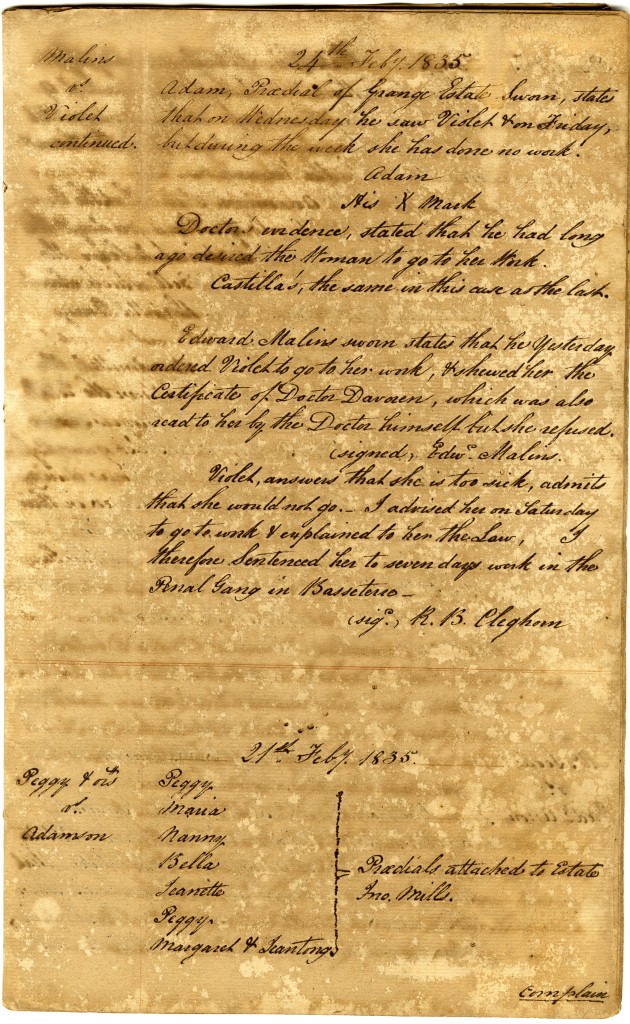

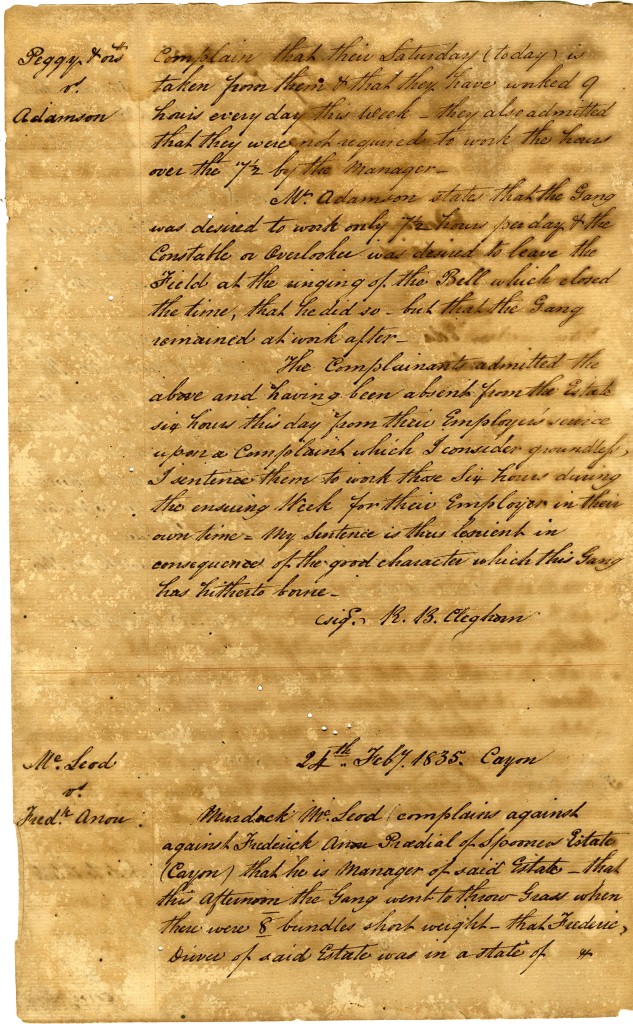

The slaves’ opposition to apprenticeship had the support of most of the free coloureds and of some of the white population. However, this was not enough to cause the abandonment of the idea. Slave discontent caused social unrest in St. Kitts in 1834. As a concession to the new apprentices, the Governor of the Leeward Islands appointed Ralph Cleghorn as Special Magistrate.

Ralph Cleghorn died on the 17th March 1842.

James Cardin

James Derrick Cardin also known as Jim Cardin or Johnnie Bull was born on November 13, 1871. He was one of several children of Alma Demming, a street sweeper. His father was the manager of Canada Estate.

The family income being small, Jim did not receive much of an education. However, things would soon change. One day while walking down Fort Street, Jim could not resist the temptation to pick a few roses from the Auld sisters’ garden. He was caught and after a frightened apology and an explanation of his mother’s poverty he was sent on his way with the flowers. Jim was then eleven years old. Later the sisters looked up Alma Demming and asked her to allow Jim to live with them. Seeing this as an opportunity to ease the burden of maintaining a large family on a meagre income, Alma agreed. As the sisters ran a school, the young boy was soon able to make up for the lack of education in his early years.

At fifteen years of age Jim signed on as a sailor to the southern islands. Eventually the Aulds sent young Cardin to the USA where he worked mostly as a Pullman Porter eventually rising to the position of head porter of the Wagner Palace Car Company which operated luxury railway carriage between New York and Washington DC.. Working on the trains brought him into contact with many wealthy and famous people such as the Vanderbilts, the Roosevelts and Bishop Dean of Albany. He also met Gene Stratton Porter, a millionaire, whose personal valet he became. James Cardin worked hard in the US and invested his savings wisely. This enabled him to return to St. Kitts after 18 years of service to personally look after his aging guardians, and to open a bookstore on Fort Street.

While in the States he found time to learn boxing and became a sparring partner to the renowned heavyweight, John Jeffries. He also traveled to England and France. He developed long lasting relationships with the persons he served. Cardin was a generous man, who was interested in the welfare of young people. He urged them to study and lectured them on the importance of education and the value of such qualities as honesty, good manners and politeness. When the Mutual Improvement Society opened a Library, Cardin, who was an honorary member, donated half of the books that were made available to members. He assisted many experiencing financial difficulties, often helped to settle disputes, and facilitated the schooling and employment of many persons. He was also willing to speak frankly to persons in authority regarding the needs to the community. Governor Fiennes in particular was, from time to time reminded by Cardin of what St. Kitts lacked.

Cardin was often deeply distressed by the stream of beggars he saw every Saturday morning in the streets of Basseterre and he did not cease in his effort to impress on the government to build a house for them. His efforts met with success in 1927 when Governor St. Johnston opened the Infirmary to admit the first inmates. Cardin volunteered to serve on the management committee and was appointed its chairperson, a position he continued to hold till 1953 when illness forced him to retire. Jim Cardin’s hallmark was charity and he could be seen daily going through the wards giving good cheer and distributing gifts for the comfort of the residents. In recognition of his untiring interest Administrator Burrows had the institution renamed The Cardin Home.

In 1918 Cardin became a member of the Freemasons by joining the Mount Olive Lodge in Basseterre. He was an ardent mason and worked hard to revive the interest in Masonry in the island. So active was he in the work of the Lodge that within a few years he had risen to the position of Master.

He was honoured with an MBE for his services to the Community. He also received a Coronation Medal from Queen Elizabeth II and a visit from President Theodore Roosevelt and Mrs. Roosevelt while they were touring the Caribbean.

James Cardin died on the 15th May 1954 after a six-month illness. In his will he bequeathed a sum of money to the Infirmary to provide two treats a year for the inmates for ten years after his death. This gesture continues to be carried out by the Brethren of the Mount Olive Lodge.

Lady Allen

Annie Maude Matilda Locker was born in Montserrat on the 20th March 1893. She was the eldest of three daughters of Police Sergeant Michael Locker and his wife Ellen. Annie’s early education was in Montserrat and Antigua. She came to St. Kitts at the age of twelve years when her father who served in the Leeward Islands Police Force was transferred to the Dieppe Bay police station. Annie attended the Bethel Moravian School and in 1909 became a pupil teacher at the Dieppe Bay Methodist School. This meant that she taught a class and afterwards was tutored by the head teacher in preparation for the examination which had to be taken every year. This was a condition for anyone who wanted to remain in the service and advance to appointment as an Assistant Teacher.

As a pupil teacher, Annie was paid six shillings and eight pence a month and this was increased to eight shillings and four pence (approximately $2.00) when she became a second year pupil teacher. She was transferred to Sandy Point Girls’ Primary School and then to Charlestown Primary School as her father was called to serve in one police station after another. Meanwhile her mother taught her sewing and needlework and she also took piano lessons.

While teaching in Charlestown, Locker won a scholarship to the Spring Gardens Teachers’ College in Antigua. This College was a training school for female teachers in the Leeward Islands, and offered annually one scholarship to third-year pupil teachers.

Following graduation, Locker returned to Charlestown Girls School as an Assistant Teacher. She then served in Dominica for a short time and was later appointed as head teacher at Old Road Primary School. In January 1927 she was appointed head teacher of Sandy Point Girls’ School where she served until 1944. However in 1937 Annie Locker had married Milton Allen and had taken long leave to accompany him to New York. While in the Unites States she pursued studies in teaching and industrial arts at Columbia University.

Mrs. Allen was painfully aware of the emphasis on theory and the lack of practical applications within the education system. In order to compensate for this deficiency, she often provided at her own expense, the necessary material and equipment required to introduce Domestic Science and the different techniques of embroidery at her school. On the other hand, her husband, who for a while continued to live in New York, supplied her with published sheet music for her school concerts. These concerts she organised in collaboration with John Edgar Hanley, Head teacher of the Sandy Point Boys’ School.

It was during this time that she founded the first Girl Guides Company in the rural area. Her main objective was the development of self-worth among girls and young women. This she attempted to achieve by encouraging the girls entrusted to her care some of whom at various times lived in her household, to participate in activities that broadened their horizons. She often warned them: “It is better to wear out than to rust out.” The Third St. Kitts Guide Company was made up of predominantly country girls from working class backgrounds. Urged by their founder, they attended every rally and meeting to keep abreast of developments in the world at large.

In the days when private vehicles were few and public transportation practically non-existent, she along with her students, still managed to attended concerts and cultural events in Basseterre. Her good relationship with people of all classes usually guaranteed a ride home at the end of the evening. In Sandy Point and the surrounding communities, Mrs. Allen was a highly respected person and there were many households where decisions would not be taken unless she was consulted.

On the 6th January 1945, Mrs. Allen was appointed the head teacher of the Basseterre Girls’ School which at the time had a roll of five hundred students and a staff of fifteen mostly pupil teachers. Her interest in extra-curricular activities continued and she was able to organize a teachers’ choral group which regularly produced concerts that attracted enthusiasts island-wide. She also played the violin and was a member of the Basseterre Players, a theatrical group while serving on the Board of Education. In 1951 Mrs. Allen became the first primary school teacher to be awarded an honorary title of Member of the British Empire (MBE). Two years later she retired from active teaching.

Her retirement from the field of formal education did not mean the end of Mrs. Allen’s involvement in the community. Social and church work continued to keep her busy. She even served as Guide Commissioner for a time. She kept in touch with young people and old friends and never forgot a girl she had taught.

In 1969, when her husband became the first national of the state to serve in the position as Governor she was able to support him in his official duties. Her excellent conversational skills, her refined good manners and taste for good clothes stood her in good stead. Sir Milton and Lady Allen brought a special dignity to the office and this was warmly appreciated by the citizens. Nor were former colleagues forgotten. On the 6th March 1975, Lady Allen realised her desire to entertain teachers at Government House. Among those attending the “at home” were several retired teachers who had been students of Lady Allen. On that occasion she spoke with pride about the role of the teacher but also gave a word on admonition:

I shiver when I hear so many unpleasant remarks about the children of today, when by my experience, I feel the blame should fall on the parents and the teachers of today.

Following Sir Milton’s retirement from public office in 1975, they moved to their private home in Fortlands. Lady Allen died peacefully at the J. N. France General Hospital on 19th February 1979.

Edgar Bridgewater

Edgar Samuel Bridgewater was born at Westbury, Nevis on 3rd October 1900. He was one of eight children born to George Bridgewater and his wife Amanda. As the father was a policeman, the family moved around a great deal. Edgar first emigrated with the family to Antigua, where he attended the Buxton Grove Primary School. At twelve years of age, young Edgar was taught by his father to play the organ. He came to St. Kitts in 1912, continued his education and at thirteen years of age he became a pupil teacher. In 1915, he returned to Nevis where he worked as a tailor. Then two years later he settled in St. Kitts and joined the Defense Force. The First World War was then raging in Europe and the Government in the colony set about the establishment of an enlarged force. Machine gun sites were established at various strategic locations and a state of military readiness was maintained by regular alarms and surprise calls. Bridgewater served as one of a crew of ten manning a gun sent by the Canadian government to protect its shipping line on which St. Kitts was a port of call.

The decade from 1920 to 1930 found Bridgewater living in Dominican Republic. While there he teamed up with W.J.E. Butler, another Nevisian, to train the Moravian Choir officiating as its organist whilst Butler was its director. He also became heavily involved in the Marcus Garvey Movement and soon found himself functioning as Assistant Secretary of the United Negro Improvement Association.

The Garvey Movement became the target of suspicion by the Americans who then occupied Santo Domingo. One Friday night as the choir practiced, they were all arrested and charged with incitement. Bridgewater spent thirty days in jail and at the end of that period he found himself the leader of the movement.

Returning to St. Kitts in 1930, Bridgewater again joined forces with Butler and became a member of both the Esperanza Band and of the Defense Force. He continued to pursue music with a passion and in 1938 formed the Defense Force Band and took on the role as its Bandmaster.

He also increased his knowledge through correspondence study and qualified for the post of court stenographer at the Basseterre Magistrate’s Court. In 1939 he joined the Civil Service as a temporary clerk attached to the Labour Office. And eight months later was appointed Chief Officer of H.M. Prison. In June 1941 he attended a Prison Officer’s training course in Trinidad and was accorded a special mention for passing out at the top of a class of forty-five. In 1942 Bridgewater was appointed Keeper of the Prison succeeding Knight as prison superintendent a position he continued to hold till 1958. In this capacity he was instrumental in the establishment of the Prison farm in Nevis.

His increased work load did not diminish his interest in music and he continued to serve as leader of the Defense Force Band producing many of the finest musicians on St. Kitts.

When Police Commissioner, John Lynch-Wade attempted to give the Police Force a wider social base, he called Mr. Bridge out of retirement to establish the Police Band. For years that band under Bridgewater’s guidance, participated in festivals under the name of Police Brass. When the band made its last march in 1980, Mr. Bridge then 80 years of age marched at the front. In 1983 Bridgewater went on to launch the Nevis Symphonic Band to which he was still giving Bridgewater also owned and operated a music shop on Burt Street but his activities in St. Kitts went beyond music.

The Prison Keeper before him ran a small penny bank for the poor people of the Methodist Church. Perhaps this was the inspiration behind the St. Kitts Industrial Bank. Along with Stanley Procope, Bridgewater promoted the idea and established a banking office on Central Street.

Hilda Bridgewater tells how, in the first few days of the enterprise, her husband asked her to lend him $40.00 so that he could make a loan to a client. When she expressed concern, Bridgewater told her that the Lord would take care of things. The Penny Bank as it was called allowed its customers to open an account with just one penny and many, who had experienced difficulties in dealing with the foreign banks, took advantage of the possibility of saving for a rainy day. It was this institution which was later to become The St. Kitts Nevis and Anguilla National Bank of which Edgar Bridgewater was a founding member. In a message published on the 20th Anniversary of the founding of the National Bank, Bridgewater recalled those early days,

You can imagine how the Bank clerks where we kept our accounts, used to ‘eye’ us whenever we turned up with these bundles of pennies to deposit. Often times we were left for the last to be served and as we watched them counting those pennies we got the feeling that they regarded our business as some sort of nuisance business.

Bridgewater also served as a member of the Central Housing Authority at a time when it was engaged in promoting aa improved standard of housing at an affordable price for working class people. He was also the Chairperson of the Public Service Commission.

Edgar Bridgewater died in Nevis at the age of ninety-five years on Thursday, August 29, 1996.

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram