The Stamp Act Riots of 1765

The British victory in the Seven Years War (1756-1763) had been an expensive one and when it was over Britain decided to maintain an armed force in North America to safe guard its new acquisitions. The Stamp Act was introduced to meet this cost. It was a tax on legal documents which would be null and void without it. However the tax fell heavier on the Caribbean colonies and brought no real benefits to the islands where the military presence was actually reduced. Moreover the colonists in the islands insisted that taxes had to be raised through their elected assembly

After night fall on 31st October 1765 a crowd of three to four hundred gathered at Noland’s Tavern and to the beating of a drum marched to the home of John Hopkins. He was a local merchant and deputy stamp distributor in St. Kitts. The boisterous crowd demanded that he turned over the stamp papers and then burnt them in front of his door. Hopkins was then forced to resign his post and to lead to mob to the place where William Tuckett, the Stamp Distributor was staying. The place was about three quarters of a mile out of town. Although he was sick with fever, the crowd put Tuckett on a horse and brought him back to the market, then located in College Street. The Stamp Distributor was roughly handled and almost trampled but for the assistance of some black people who were near by and who helped him get out of town

The mob then went to the office of the island secretary and also to the office of the deputy provost marshal (probably on Church Street) where more stamp paper was burnt. Then they headed to the customs house then located at the bottom of College Street where the collector of customs persuaded them to leave after he declared over and over that he had no stamp paper. The disturbance went on through the night and supporters of the act were verbally abused. Approximately two thousand pounds sterling were destroyed that night.

While this was going on Tuckett fled to Nevis and on the 2nd November he started to distribute stamps. Kittitians followed him there and along with Nevisians who opposed the Stamp Act, they embarked on a trail of destruction which saw two houses burnt. The stamp paper that they got hold of was placed in a navy long boat and the whole set on. fire.

On the 5th of November, instead of burning the effigy of Guy Fawkes, the islanders gathered on the pasture in Basseterre (now Independence Square) and burnt figures representing the Stamp Distributor and his deputy. That evening many assembled for an elegant dinner which closed with the toast “Liberty, Property and No Stamps.” New supplies of stamps were not allowed to land on St. Kitts by those who continued to oppose the Act.

A joint committee of the Council and Assembly was later set up to investigate the riots but it failed to take action as the members of both bodies were in sympathy with the rioters.

The story of the riots in Basseterre, was carried by a number of newspapers in the north American colonies including the Massachusetts Gazette, the Boston Gazette, the Boston Post Boy and was part of an anti tax movement that swept the English colonies in North America.

Destruction of War

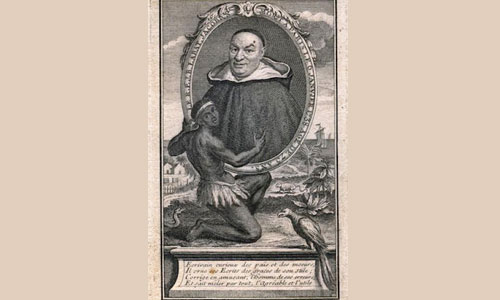

Selection from Père Nouveau Voyages aux Isles de l’Amerique 1693-1705 (Paris, 1722)

J’allai me proéminer sur le soir aux environs du bourg. Il paraissait par les mesures et les solages des maisons qu’il avait été autre fois bien bâti et fort considérable. Les Anglais l’avaient entièrement détruit, jusqu'à transporter chez eux les matériaux et les pierre de taille et les pierres de taille des encognures. Nos Français avaient déjà rebâti beaucoup de maisons et travaillaient a s’établir comme s’ils eussent été assures d’une paix éternelle.

(In the evening I walked in the vicinity of the town. From the size and foundations of the houses it seems that that they had been strong and well built. The English had completely destroyed the place to the point of carrying away building material and corner stones. The French had already rebuilt many houses and worked as if they had been assured of eternal peace.)

Medical Attention given to Enslaved Workers

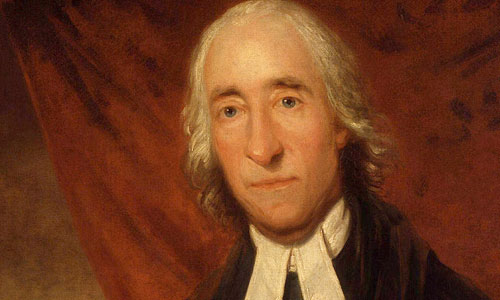

Selection from - Rev. James Ramsay, Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies (London: James Phillips, 1784).

A surgeon is generally employed by the year to attend the sick slaves. His allowance per head varies from fourteen pence to three shillings; in a few instances it rises tp three shillings and six pence sterling, besides being paid for amputations. Some frugal planters trust to their own skill, and James’s powder and Ward’s pill’ and, then, for the most part a surgeon is only called to pronounce them past recovery.

The food of the sick is often musty, indigestible horse beans, sometimes maize, flour, or rice; sometimes, as a dainty, brown biscuit, on some plantations, the manager is allowed to get, now-and-then, a fowl, or a kid to make soup for them. Sometimes the owner sends the manager a cask of wine, a few glasses of which are supposed to be for the use of the sick. Where the manager is a married man, the sick often have a mess from his table, and caudle, tea, and other comfortable slops; and his wife superintends the conduct of the nurse and sees that the pregnant and lying-in women be properly taken care of. But the custom of employing married man on plantations is wearing fast out. (Pages 82-83)

We cannot pass over in silence the usual treatment of pregnant women and nurses. In almost every plantation they are fond of placing every negro who can wield an hoe in the field gang; so fond, that hardly any remonstrance from the surgeon can, in many cases, save a poor diseased wretch from the labour; though, if method prevailed, work may be found on the plantation equally necessary and proportioned to every various degree of ability; and though one or two days attempts in the field be sure to lay them up in hospital for weeks.

At this work are pregnant women often kept during the last months of pregnancy, and hence suffer many an abortion; which some managers are unfeeling enough to express their joy at, because the woman on recovery, having no child to care for, will have no pretence for indulgence.

If after all, she carries her burden the full time, she must be delivered in a dark, damp, smoky hut, perhaps without a rag in which to wrap her child, except the manager has a wife to sympathize with her wants. Hence the frequent loss of negroe children by cramp ad convulsions within the month. A lying-in woman is allowed three, in some plantations four weeks for recovery. She then takes the field with her child, and hoe or bill. The infant is placed in the furrow, near her, generally exposed naked, or almost naked, to te sun and rain on a kid skin, or such rags as she can procure. Some very few people give nurses an extra allowance. In general, no other attention is paid to their condition, except perhaps to excuse them from picking grass. (page 88-89)

To read more of this publication, please visit Google Books

Comments on the Cunningham Hospital

Selection from John Davy The West Indies Before and Since Slave Emancipation (London: W & F G Cash, 1854)

In another island, St. Kitts, the Civil hospital was as much open to censure for opposite qualities, which, even now, I fear, are only partially corrected. When I visited it was in a very discreditable state; dirty and disorderly and ill provided, more likely to be productive of, that to promote the cure of disease, to increase that to alleviate suffering; and this owning not so much to want of funds, as to neglect and mad management. Under any circumstances lamentable in this instance it was the more so, as the building new and neat and not ill fitted for the purpose for which it had been constructed, was a boon to the island from ta deceased Lieutenant Governor, the late Mr. Cunningham, who provided the funds expended on its erection. (page 521)

You can read more of this publication at Google Books

Universal Benevolent Association

In 1916, in the middle of the First World War and in the face of low wages and attempts to limit emigration to Cuba and the Dominican Republic, Joseph Nathan organized a petition requesting uniform wages for agricultural workers and government regulation in setting the size of tasks and hours of work. However the Administration felt that it had no right to interfere in relations between a planter and his labourers. In November of that same year, undaunted by this response and perhaps even motivated by it, Nathan and others announced the formation of a trade union. Combining the objectives of a trade union and a benefit society, the organizers set as their goals the unity of all classes of labourers, the achievement of fair wages from all employers, the provision of a Christian burial, and assistance for the sick and injured members.

Dues consisted of a one time registration fee of one shilling, then weekly subscriptions of 8 pence for tradesmen, 6 pence for male labourers and 3 pence for females. Those joining were expected to be disciplined and law-abiding at all times and to respect the decisions of the Governing body especially in matters concerning wage negotiation and industrial action.

The organizers of the new union were self-employed businessmen. The first president was Frederick Solomon a contractor and undertaker who had been motivated by workers’ complaints about low wages. The other officers were Joseph Nathan, the owner of the International Supply Association, a small retail business and George Wilkes, a barber. Both Nathan and Wilkes had lived in the United States for some years and had experienced the humiliation of racism and the benefits of organisation in the work place. These life-lessons governed their attitude towards the planters and the Administration. Also among the organizers were William Seaton and A. St. Clair Podd both with strong connections to the merchant class and with concerns that were of a philanthropic nature. Their presence in UBA was short lived although they continued to take an interest in the welfare of workers.

On the 22nd November 1916, the legislature passed the Trades and Labor Unions Prohibition Ordinance through all its readings. The new law imposed a fine of £50 or 6 months imprisonment on anyone attempting to form a trade union and was to last for the duration of the war. It was felt that the formation of a Union would lead to strikes and riots. There was also grave concern over the indubitable involvement of shiftless labourers returning from the Dominican Republic. Included were men who would have been waiting in Basseterre for transport to neighbouring islands as St. Kitts was then a drop off and pick up point.

Despite the new law and the general hostility of the planter class, Solomon, Nathan and Wilkes decided to continue their efforts to organize the workers. To get around the recently passed ordinance they created a friendly society – the Universal Benevolent Association. Solomon became the first president, Nathan its secretary and Wilkes held the post of treasurer. By August 1917, they claimed they had a membership of 1500 and £208 in benefit funds. The Association’s main objective was the repeal of the Masters and Servants Act of 1849. This law saw as a criminal offence, the breach of the work contract by a labourer, however an employer who broke his contract with his workers was only liable for damages or wages owed, therefore his breach was only a civil matter. While recognizing the need to review the Act, the Colonial Office did not want to seem to be giving in under pressure.

Meanwhile the UBA continued its efforts to organize estate workers but with limited success. In October 1917, workers at Willett’s and Belmont most of whom lived in St. Paul’s went on strike. Nineteen of them were called to face charges of breach of contract, or as the workers called it “Bridge of Contract” under the old law. Magistrate Wigley fined each of the defendants eight shillings or ten days imprisonment. The workers refused to pay the fines and walked to Basseterre to serve their sentence. The UBA appealed for their release but without success. Administrator Burdon refused to intervene as the St Paul Martyrs had deliberately chosen imprisonment.

The Administration was clearly aware of the root cause of these developments. The high cost of necessities had not been matched by increased wages and yet the planters continued to make great profits. To avoid further problems, the Acting Governor requested a wage increase to allow workers to better cope with war prices. Reluctantly the planters yielded.

Frederick Solomon died suddenly in 1918 and the mantel of leadership was taken up by J. Matthew Sebastian, who up to that point had been a teacher. Sebastian was also responsible for publishing The Union Messenger. The name of the newspaper was a reflection of what people thought the role of the UBA was supposed to be.

The concept of trade unionism was new in 1916. Workers tended to become organized on impulse as the frustration over low wages and poor conditions reached boiling point. Once their anger had been vented and the arrests, that inevitably followed, were made, then a calm would return, until the next time they became frustrated. The organizers of the UBA were offering sustained organization and collective bargaining power, but it was going to take a disciplined and educated workforce to recognize the advantages of unionization. This came about in 1940 when the first Trade Union was registered under the Trade Union Ordinance of 1939 and found its strength in the sustained collective efforts of the sugar factory workers.

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram